‘Built to burn.’ L.A. let hillside homes multiply without learning from past mistakes

- Share via

On a hot, dry November morning in 1961, flames from a trash pile on brushland north of Mulholland Drive were picked up by Santa Ana winds and swept across the canyons of one of Los Angeles’ wealthiest enclaves.

The apocalyptic scenes that played out — of Hollywood celebrities fleeing and clambering onto their roofs — captured the world’s attention like no urban conflagration in history. Actor Kim Novak and Richard Nixon, then a former vice president who moved to L.A. to practice law, wielded garden hoses to soak their wooden roof shingles. Actor Fred MacMurray enlisted studio workers from the set of “My Three Sons” to evacuate his family and help firefighters cut down brush around his Brentwood home.

When the blaze reached the mansions of Bel-Air, thermal heat lifted burning shingles high into the air and 50-mph winds hurled them more than a mile over to Brentwood. By nightfall, the Bel-Air fire had destroyed 484 homes, including those of actor Burt Lancaster, comedian Joe E. Brown and Nobel laureate chemist Willard Libby.

After firefighters extinguished the flames, socialite and actor Zsa Zsa Gabor, wearing white kitten heels and a string of pearls as she clutched a shovel, dug through the rubble of her Bellagio Place home for a safe with jewels.

The Bel-Air fire became known as the “the big one,” the event that forced everyone in Los Angeles to reckon with the dangers fire posed to their coveted hillsides.

In response, L.A. officials ushered in new fire safety measures, investing in more firefighting helicopters, new fire stations and a new reservoir. They also outlawed untreated wood shingles in high-fire-risk areas and initiated a brush clearance program to create defensible space around homes.

But they did not stop building on fire-prone ridges and canyons.

And there was no major push to radically rethink how they built. Over the next half a century, new housing tracts filled the wildland interface. And a succession of larger and more deadly fires swept through the region. But all the safety improvements prompted by the Bel-Air and subsequent fires could not outpace the escalating threat from new development and climate change.

The massive blazes that engulfed Los Angeles hillsides communities Jan. 7, destroying 16,000 structures and killing at least 29 people in and around Pacific Palisades and Altadena, have prompted a new reckoning on how so many L.A. homes came to be built on land so vulnerable to fire and how, or whether, they should be rebuilt.

It’s a crossroads the region has found itself at before when the power of fire left us reeling.

“California is built to burn — it’s not unique in that — but it’s built to burn on a large scale and explosively at times,” said Stephen Pyne, a fire historian and professor emeritus at Arizona State University.

“You can live in that landscape, but how you choose to live will affect whether that fire is something that just passes through like a big thunderstorm, or whether it is something that destroys whatever you’ve got.”

::

The story of how Los Angeles developed itself for disaster began with careless building on hillsides more than a century ago.

As the emerging metropolis began to overtake San Francisco as the most populated city in the West, shrewd real estate developers began to cast their eyes up to the foothills of the Santa Monica and San Gabriel mountains.

“The future of Los Angeles is in the hills,” proclaimed a 1923 ad for a new subdivision that showed renderings of Spanish Revival-style homes looming over steep hillsides and bluffs. “Hollywoodland will soon be a tract of beautiful homes with magnificent views.”

Lots cost as little as $2,000 — the equivalent of about $36,000 today.

The 1920s were a boom time for L.A., an era of heady confidence in humans’ ability to reshape the natural environment. The 1913 construction of the Los Angeles Aqueduct, a bold engineering feat that transported water more than 230 miles to the semiarid region, paved the way for more than 100,000 people to move into the city each year. As the automobile allowed a burgeoning new middle class to live farther from downtown, the hills no longer looked so remote.

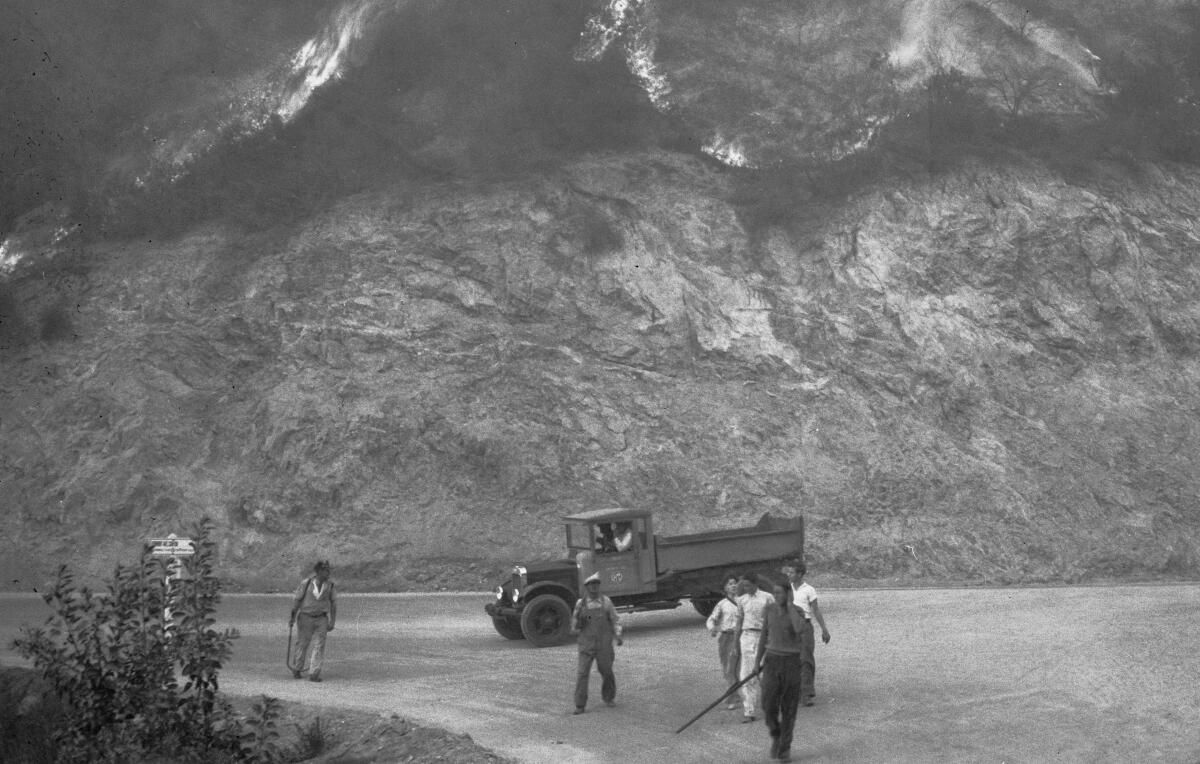

Hollywoodland may have been the most cannily marketed hillside subdivision: Its developers — including Harry Chandler, then publisher of the Los Angeles Times — erected a 45-foot-tall sign on Mt. Lee and invited reporters to chronicle the blasting of granite with dynamite and the cutting of roads with steam shovels.

But all over the mountains surrounding L.A., developers were buying up ranchland, filing plat maps and producing lavish real estate ads and sales brochures touting the foothills as an elevated paradise for a newly emerging upper middle class.

Bel-Air marketed itself as “the Exclusive Residential Park of the West” — so exclusive its owner refused to sell to members of the motion picture industry. Beverly Wood touted itself as “the Switzerland of Los Angeles.” Pacific Palisades, founded by Methodists, was a “Christian community” with modern amenities “where the mountains met the coast.” In Altadena, a railroad hub in the shadows of the San Gabriel Mountains, Altadena Woodlands offered “a garden spot” and “panorama of wondrous beauty.”

In all the marketing hype, there was no mention of the risk of fire and landslides.

“It was a period of almost zero environmental consciousness,” said Philip Ethington, a professor of history, political science and spatial sciences at USC. “They had a poor understanding of the long, long history of fires, and the long ecological necessity of them. The developers didn’t want to dwell on the hazards. They saw fires as freak events.”

L.A.’s sloping suburbs came to embody not just the city’s ambition but its folly.

Many hillside homes were built with combustible wood shingle roofs. They were crowded together, next to flammable brushland, and accessed by narrow, winding roads that struggled to accommodate two-way traffic or firetrucks. Some communities had only one way in and out.

“To be in the hills, to be outside the madding crowd, this is part of the DNA of this region,” said Zev Yaroslavsky, a former Los Angeles County supervisor who represented L.A.’s foothills from 1994 to 2014. “In a way, Los Angeles itself is an engineering feat: It’s an accidental city that was promoted by the sense that anything is possible. But the engineers also didn’t fully anticipate the implications of what they were doing.”

For thousands of years, Indigenous people lived in L.A.’s mountains. Some settled in the village of Topaŋa, a mile up the coast from what is now Pacific Palisades.

But native Californians who were drawn to the woodlands at the base of mountains had a different relationship with fire, Ethington said; they chose not to live in the narrow canyons that were flood-prone and dangerous fire traps when dry Santa Ana winds blew.

“They knew it’s perilous for basic reasons: It’s a Mediterranean environment that has a necessary regular annual drought,” Ethington said. “Most of the rain falls within a few months … and then the rest of the year is dry, so it’s highly flammable.”

Every year, Indigenous people set small low-intensity fires to manage the landscape and clean out low-lying brush — a process that magnified the yield of their plants for medicine and craft-making. It also helped to prevent intense crown fires.

The Spanish colonizers suppressed this intentional annual brush burning, claiming it was incompatible with agriculture. In 1850, when California became the nation’s 31st state, legislators passed the Act for the Government and Protection of Indians, which prohibited intentional burning in prairie lands.

But the move to suppress fire, some experts say, only magnified the risk of more destructive blazes.

Some L.A. officials sounded the alarm in the height of the 1920s building boom.

In 1923, less than six months after construction began in Hollywoodland, L.A.’s fire chief pushed for an ordinance prohibiting wood shingles after a wildfire destroyed nearly 600 homes in the foothills of the Northern California city of Berkeley.

“Without a doubt,” the city building inspector told the L.A. Times, “the prohibiting of wood shingles should extend from the eastern limits of the city to the outer edge of Hollywood.”

But the lumber industry came out in force against a ban, ultimately persuading L.A. and California not to act.

In 1930, city leaders got another warning — this time closer to home.

“FLAMES ROARING THROUGH SANTA MONICA HILLS,” the front page of The Times declared Nov. 1, 1930, as nearly 1,000 men battled a towering wall of fire that blazed south across the Malibu coast. “MAJOR DISASTER LOOMS.”

The wildfire was 25 miles away. But if strong north winds continued to blow, The Times reported, the blaze would engulf remote mountain areas inaccessible to firefighters and fuel up on dense brushland. Firefighters, officials feared, would be helpless to stop it sweeping through Topanga and destroying many of the newly built homes across Pacific Palisades and Hollywood Hills.

Alarmed, L.A. County Supervisor Henry Wright rounded up 100 men to patrol the edges of the city. If the fire got “close into the city of Los Angeles,” Wright said, “our whole city might go.”

Ultimately, the north winds subsided and hundreds of firefighters and volunteers got the fire under control. But with calamity averted, there was little debate on how to avoid future brush fires from tearing through L.A.’s foothill communities.

Wright, the new chair of L.A. County Board of Supervisors, emphasized the need for “an improved method of preventing disastrous forest fires” and developing a county building code and “intelligent zoning.” But a year into the Great Depression, unemployment was the county’s biggest priority. The county created a fund for hundreds of men to work on firebreaks. Beyond that, there was little effort to rethink how, or whether, to build homes in fire-prone hills.

After World War II, economic growth and GI benefits fueled another rapid building boom. As people moved to new subdivisions on former ranchland in the San Fernando Valley, hillside lots were no longer on L.A.’s outskirts. They were just another, highly desirable, part of L.A. suburbia.

The risks magnified as new generations pushed farther into natural spaces, creating fire-belt suburbs.

In Pacific Palisades, already less isolated after the extension of Sunset Boulevard and the 1937 opening of Pacific Coast Highway, single-family homes ventured farther up the canyons. In Altadena, new tracts were built on farmland. In Bel-Air, the builder of a new subdivision of mid-century modern homes in Roscomare Valley campaigned for a 1952 statewide proposition to fund schools, confident that would lure more residents.

When experts from the National Fire Protection Assn. surveyed Los Angeles in 1959, “they found a mountain range within the city, combustible roofed houses closely spaced in brush-covered canyons and ridges, serviced by narrow roads,” according to a documentary produced by the Los Angeles Fire Department. “They called it ‘A Design for Disaster.’”

Just two years later, the Bel-Air fire showed the world catastrophic scenes of Los Angeles.

L.A. officials made a number of reforms. But even as L.A.’s fire chief noted the progress the city had made, including tightening restrictions on wooden roofing on new homes, he told The Times in 1967 that the bulk of homes still had shake or shingle roofs. The battalion commander of the Fire Department’s mountain patrol said they couldn’t eliminate all brush from slopes without causing erosion and landslides, and some homeowners were resistant to removing flammable vegetation: “They like it for its scenic value.”

As L.A.’s slopes filled with audacious mid-century modern steel and glass mansions and even a UFO-style octagon resting on a 30-foot pole, a national 1968 report by the American Society of Planning Officials identified “the subdivision of hilly areas” as a growing problem. Planners were under pressure, the report said, from developers trying to cut costs to modify subdivision controls with lower standards for hillside areas than flat land. If the controls were not modified, subdividers simply leveled the hills.

The problem was particularly acute in L.A.: Two-thirds of the city’s new homes were being built on hillside lots, according to a city official. All were potentially vulnerable to landslides.

The failure to provide access to subdivisions from more than one entrance, the L.A. County engineering department said in a report, “greatly endangers public safety.”

Foothills residents often resisted efforts to widen narrow, winding streets. In 1970, as new housing developments were planned across the Santa Monica Mountains, homeowner associations objected to a city master plan that would widen and extend existing canyon roads linking Sunset Boulevard and Mulholland Drive. L.A.’s city traffic engineer, Sam Taylor, argued that fire and emergency personnel must have alternative road access in case other roads were blocked.

“Either the mountains should not be developed,” Taylor said, “or we should provide streets to take care of the thousands of new homes.”

The 1970 Clampitt and Wright fires merged to burn 435,000 acres from Newhall to Malibu, killing 10 people and destroying 403 homes. The 1978 Mandeville Canyon fire destroyed more than 230 homes, killed three people and injured at least 50. In 1993, the Old Topanga fire burned 18,000 acres in Malibu, killed three people and destroyed 388 structures, prompting the writer and urban theorist Mike Davis to write his seminal 1995 essay, “The Case for Letting Malibu Burn.”

“‘Safety’ for the Malibu and Laguna coasts as well as hundreds of other luxury enclaves and gated hilltop suburbs is becoming one of the state’s major social expenditures, although — unlike welfare or immigration — it is almost never debated in terms of trade-offs or alternatives,” Davis argued in “Ecology of Fear: Los Angeles and the Imagination of Disaster.”

People continued to move into fire-prone foothills and valleys. Between 1990 and 2020, the number of homes in the metro Los Angeles region’s wildland-urban interface, where human development meets undeveloped wildland, swelled from 1.4 million to 2 million — a growth rate of 44%, according to David Helmers, a geospatial data scientist in the Silvis Lab at the University of Wisconsin-Madison.

In 2008, California significantly strengthened its building code, requiring developers of new homes in high fire-risk areas to use fire-resistant building materials, enclose eaves to stop them from trapping sparks and insert mesh screens over vents to prevent embers from getting into homes.

Experts in fire mitigation said the new building code was a huge step forward — except that it did not apply to existing development.

“We’re hamstrung,” said Michael Gollner, an associate professor of mechanical engineering at UC Berkeley who studies fire risk. “Most things are already built, and they’re built to old codes, they’re built with old land-use planning decisions, so they’re close together and not built in a resilient, fire-resistant way. It’s very hard to make changes after the fact.”

The blazes got more intense. The 2009 Station fire became the largest in L.A. County history, charring 250 square miles, destroying more than 200 structures and killing two county firefighters. The 2018 Woolsey fire destroyed more than 1,600 structures, killed three people and forced more than 295,000 to evacuate.

In 2018, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors approved a 19,000-home development in Tejon Ranch along Interstate 5 despite concerns that the land was within “high” and “very high” fire hazard severity zones. Backers say they can mitigate fire risk.

In 2020, the state Legislature passed a bill requiring households in fire-prone areas to clear anything flammable, such as vegetation or wooden fences, from within 5 feet of their home. But the rule is still not enforced.

Many homeowners — who sought homes surrounded by nature — resisted stripping their land of shrubs and trees.

Yaroslavsky, the former Los Angeles County supervisor, said he didn’t like to speculate on what L.A. officials could have done better, but it was important to learn from mistakes.

“It’s one thing to make a mistake or misjudge something or be ignorant,” he said. “It’s another thing not to learn from the consequences of that lack of knowledge.”

Looking back over more than a century of development, many blame L.A. leaders’ relentless pursuit of growth. Char Miller, a professor of environmental history at Pomona College and author of “Burn Scars,” a history of U.S. wildfire suppression, said new development was the “spark plug” for many of the region’s fires.

“We’ve created this dilemma by policy,” Miller said. “Every city council, every town hall, every planning zoning and architectural commission greenlights and rubber-stamps development because development is growth, and growth builds an economy.”

For Pyne, California’s “unholy mingling of built and natural landscapes” ultimately undermined any fire protection. But he noted that fires were caused not only by people moving into wildland areas. In Mediterranean Europe, fires are breaking out in Greece, Portugal and Spain as people move out of rural areas and small farms go feral.

Some argue that turning ranchland into public parks and conservation areas have exacerbated fire risk. According to Crystal Kolden, director of the Fire Resilience Center at UC Merced, vast swaths of the Santa Monica Mountains were ranched until the 1960s: The establishment of Topanga State Park in the 1960s and Santa Monica Mountains National Recreation Area in 1978 meant that cattle no longer grazed on shrubs, controlling flammable brush and preventing the spread of intense fires.

Even as governments introduced new fire protection measures, Pyne said, they could not seem to do so fast enough to meet the escalating threat from land-use planning decisions and climate change.

“You have to build to survive a blizzard of sparks,” Pyne said. “Fire is going to come as long as the winds are able to blow.”

After the Jan. 7 fires caused an estimated $250 billion in property damage, some make the case for a retreat: “I don’t care what you build back into the Palisades,” said Miller, who has suggested L.A. follow the city of Monrovia and float bonds to purchase lots from willing sellers. “You’re building back to burn.”

Others have proposed L.A. pause rebuilding to consider stricter construction guidelines, such as mandating even more fire-resistant materials and installing fire shutters on every home.

But the human impulse to rebuild, like the fires, is relentless.

Days after swaths of Pacific Palisades and Altadena were destroyed, Gov. Gavin Newsom and Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass issued executive orders to expedite rebuilding by relaxing environmental and regulatory obstacles.

Times editorial library director Cary Schneider contributed to this report.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.