Gilmore: a Dreamer on the Right Track

- Share via

All that we see or seem, Is but a dream within a dream. --Edgar Allan Poe

Lenn Gilmore stands in the on-deck circle of a major league stadium, studying the pitcher while awaiting his turn at bat. The crowd murmurs as Gilmore approaches the plate, settles into the left-handed hitter’s side of the batter’s box and awaits the pitch from Nolan Ryan.

Gilmore feels completely relaxed as the fastball approaches. He lets his hands start back, coils for his swing and begins whipping his bat through the strike zone.

This is when he is supposed to knock the cover off the ball, when the crowd is supposed to go into bedlam.

But like a Poe-inspired nightmare, this is where Gilmore abruptly awakens, his fantasy tauntingly unfulfilled.

“It’s a weird dream that reoccurs all the time,” Gilmore said, “I never see myself hit the ball because I always wake up. I guess I’m a little bit of a fruitcake or something.”

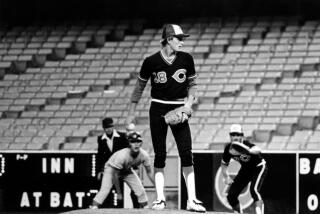

Gilmore, the parlous and lately prodigious home-run-hitting right fielder for Cal State Northridge, dreams often about playing in the major leagues and exploding on the perfect pitch. Once, he dreamed he exploded because he was a perfect pitch.

Gilmore was a sleepy sophomore at Sparks High in Nevada the day that memorable musing occurred during English class.

“I dreamed I was a baseball,” Gilmore remembered. “I think I was thrown by Don Sutton. I hit Reggie Jackson’s bat and I thought I had a heart attack. I must have jumped back four desks. He made real good contact.”

Lately, Gilmore’s reality has been close to fantasy. After finishing February without a home run, he indulged in some personal March madness by clubbing a dreamlike 11 home runs in 17 games and collecting 31 of his 40 runs batted in. The 5-foot-11, 185-pound senior surpassed his 1987 season output for home runs Wednesday with a solo shot against Cal State Los Angeles.

“I’ve had hitting streaks before, but I’ve never hit home runs like this,” said Gilmore, whose mustache and permanent 5 o’clock shadow remind one of Kirk Gibson. “Right now, I just want to sleep and wake up for game time.”

In February, Gilmore probably would have preferred to stay in bed. He was batting .180 after sleepwalking through the first nine games of the season.

The images on the videotape from a season ago when Gilmore batted .341 were of a relaxed hitter standing tall in the box and using an unencumbered swing--a figure that was disturbingly absent from this season’s tapes. Instead, Gilmore and Northridge assistant Mark Morton saw a hitter who was stiff, crouched and unable to cut loose.

Gilmore, 22, made the necessary adjustments and his swing began to reappear during the next seven games. The hits began to fall and he raised his average to .271.

Then came March 1, when Northridge traveled to USC for a nonconference game against the Trojans, then 15-2 and ranked 13th in Division I.

The Matadors won, 15-7, as Gilmore blasted three home runs--including a grand slam--off three different pitchers who threw him three different kinds of pitches. He finished with eight RBIs.

“It was remarkable,” USC Coach Mike Gillespie said. “There was nothing tainted about any of them. We really felt, particularly on the last one, that we had identified a place in his swing where we could get him. That pitch came down 430 feet later.

“He looked like Babe Ruth that day.”

Ruthian performances notwithstanding, Gilmore prefers to pattern himself after Ted Williams. He can quote theory from Williams’ book “The Science of Hitting” and is an ardent viewer of film and videotape of the Red Sox slugger.

Gilmore’s fascination with the Splendid Splinter began while growing up in Sparks, a neighboring town of Reno, named after former Gov. John Sparks. The Sparks chamber of commerce revels in the town’s railroad heritage when it boasts that Sparks is On the Right Track . That is pretty much how Gilmore felt when he graduated from high school in 1984 as a standout performer in basketball and baseball.

Lenn, the youngest of four athletic brothers, headed to Yuba City College in Northern California. He batted .410 with 5 home runs and 20 doubles as a sophomore, earned all-conference honors, and waited by the phone, hoping to hear from a major league team at draft time.

The call never came. And after hoped-for scholarships to Tennessee and Fresno State failed to materialize, Gilmore was prepared to hang up his spikes and join the family furniture business.

“I figured if I had the kind of year I had and I didn’t get a shot, then they’re looking for something that I didn’t have,” Gilmore said. “It was a tough time. I was seriously thinking of not playing.”

Randy Gilmore, who played on Northridge’s national championship team in 1984, told his younger brother that Matador Field might be a nice place to give baseball another shot. Since arriving, he has made himself at home. He earned second-team All-California Collegiate Athletic Assn. honors last season and has blossomed into the conference’s leading power hitter.

One of the keys to Gilmore’s success this season was his move from second to third in the batting order. No longer is he forced to sacrifice bunt and rarely, if ever, does he get the take sign. Curiously, Gilmore, a switch hitter, has not benefited much from the notorious winds that make Matador Field a hitter’s paradise. Six of his 11 homers were hit on the road; nine were hit left-handed.

“He’s the guy you want up there with men on base and that’s why he’s hitting where he’s hitting,” Morton said. “You don’t need to wheel everybody and make it a close play if you know Lenny Gilmore is coming to the plate.”

The other key for Gilmore has been his ability to harness his emotions. Gilmore’s father remembers the distress his son displayed on the basketball court in high school if he made a mental mistake. “He’d get down on himself and get such an ugly look on his face, the ref would give him a technical foul,” Al Gilmore said.

A case of high blood pressure during his freshman year at Yuba College taught Gilmore a lesson.

“You have to stay on the same plane emotionally,” said Gilmore, whose spirit has been tested this season playing for a Matador team that is 12-22 overall and 3-6 in conference play. “Every major leaguer who’s consistent says that.

“I used to think there’s no way you can go 0 for 5 and not be bitter. But you can. You just have to let it go and look forward to the next at-bat.”

When Gilmore feels like letting go, he often heads for the hills to hunt near Jarbridge on the Nevada-Utah border. He spends 10 days every November roughing it, sleeping under the stars and hiking through the hills in search of mule deer, quail, pheasant and other game.

“It’s relaxing,” Gilmore said. “You’re out in your own little world. To me that’s the best time to think about hitting because there’s nothing to distract you. You don’t have the phone ringing and you don’t have an 8 o’clock class to get up for. Every year I’ve done that, I’ve just come back and hit the . . . out of the ball.”

Gilmore has 21 games left to continue his assault. After this season, he plans to keep his piercing blue eyes focused toward the draft.

“Wherever I’ve gone, I never started out as the best, but by the time I was done at the place, I was the best,” Gilmore said. “That’s why I want a chance to play pro ball. Because if I can continue to do that, I have a chance to keep moving up.”

If it happens, it will be the realization of one dream. Only then, perhaps, will Gilmore be able to see his other one through to completion.

“I’m curious,” Gilmore said. “The pitch that’s always coming is a perfect pitch and I know I’m starting my swing at the right time. I have the feeling it’s a home run, but I’d like to actually see it go out once.”

More to Read

Go beyond the scoreboard

Get the latest on L.A.'s teams in the daily Sports Report newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.