D. A. Testifies He Socialized With Fraud Suspect : Courts: Ira Reiner says he broke off contact with Mark Weinberg in 1985 after learning that the commodities broker was under criminal investigation.

- Share via

Dist. Atty. Ira Reiner, who had unsuccessfully attempted to avoid testifying in the trial of a former associate linked to organized crime and charged with defrauding investors, said in court Tuesday that the two socialized and went to the 1984 Olympics together.

But Reiner declared in Van Nuys Superior Court that he broke off all contact with Mark D. Weinberg, 37, in July, 1985, after learning that the former Beverly Hills commodities broker was the subject of a criminal investigation.

The district attorney, who accepted more than $250,000 in campaign contributions from Weinberg in 1984, was not asked in court to give details of the investigation and refused to give any in an interview outside court.

No charges were ever filed as a result of the earlier investigation, and there appears to be no link to the current case in which Weinberg is accused of bilking wealthy investors.

Reiner arrived 90 minutes early for his court appointment, giving only 20 minutes notice to court officials and left immediately after his 15 minutes on the stand.

Weinberg’s organized crime connections--and his claim that he informed for the FBI against the mob--have come up several times in the 3-week-old trial. Those links also reportedly were the subject of at least one closed session in Judge John S. Fisher’s chambers at which two FBI agents testified.

Deputy Atty. Gen. Tricia Ann Bigelow, who is prosecuting the case, argued at one point in open court that Weinberg should “not be allowed to introduce the fact that he worked for the FBI in the early ‘80s.”

Also scheduled to testify at the trial are Mayor Tom Bradley, who accepted $84,000 in campaign contributions from Weinberg in the mid-1980s, and Sen. Alan Cranston (D-Calif.), who was hosted at a plush fund-raising party at Weinberg’s Beverly Hill home.

Spokespersons for Bradley and Cranston said earlier that, like Reiner, they broke off contact with Weinberg on learning in the mid-1980s that he was the subject of criminal investigations.

Reiner, who is facing a likely reelection primary challenge in less than four months, had sought to avoid testifying in the case.

But Fisher refused his petition, permitting Weinberg, who is representing himself, to call Reiner, Bradley and Cranston to rebut what the judge termed as suggestions by prosecution witnesses that the defendant had been a “name-tosser” who falsely claimed to have friends in high places in order to lure clients into risky investments.

Reiner’s court appearance was closely watched Tuesday by allies of several prospective opponents in the June 2 primary, largely because earlier statements by Weinberg indicated that he might bitterly criticize the district attorney in court.

There also was speculation that, as part of his defense, Weinberg might seek to convince the jury that Reiner’s office was prosecuting him to disassociate the district attorney from him or to avoid repaying a $50,000 loan that Weinberg made to Reiner’s campaign in 1984.

The district attorney’s office initially filed charges against Weinberg but turned the case over to the California attorney general’s office because of a possible conflict of interest stemming from the defendant’s campaign contributions.

On the stand, Reiner acknowledged the loan, but Weinberg surprised political observers by not asking him why he had waited until six months ago to repay the money. A Reiner campaign official said in an earlier interview that the money was not repaid for seven years because it was thought to be a contribution.

Weinberg also did not follow through Tuesday on his threat to ask Reiner to confirm that he had aided the district attorney in securing refinancing for his house--a claim that the district attorney flatly denies.

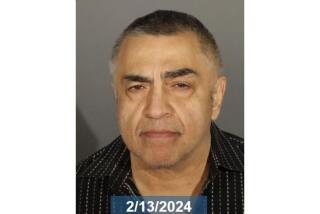

Weinberg, who is in jail in lieu of $850,000 bail, said in an interview conducted through one of his court-appointed investigators that Fisher prevented him from asking about Reiner’s house, ruling at a conference at the bench that it was irrelevant.

Over the years, Weinberg has made no secret of his mob ties.

In several interviews, he has said that he was the subject of FBI investigations in the early and mid-1980s because his business contacts included Matthew (Matty the Horse) Ianniello, Anthony (Fat Tony) Salerno and other purported leaders of the Genovese crime family.

And in 1988 and 1989, he sought to capitalize on those links by producing two crime-oriented television shows, including 29 episodes of “Crime Time,” a variety show that featured felons as guests, according to court testimony.

None of the shows, which feature lower-level mobsters discussing past crimes, has ever been sold for broadcast, Weinberg testified, but he said efforts are continuing.

However, the links to organized crime have only a tenuous connection to the four counts of grand theft and eight counts of writing bad checks that Weinberg faces.

He is accused of bilking investors by taking large sums from them on the promise that he would use the funds in a foreign currency trade, then return the money to them within days, usually with a profit of 25% or more.

Bigelow, the prosecutor, said Weinberg gambled away much of the money in Las Vegas.

Alleged victims of the schemes include James Aubrey, former president of CBS, and John Paul Jones De Joria, president of John Paul Mitchell System, a Santa Clarita-based hair products company.

On the stand, Weinberg said he was the victim of business reverses, including his inability thus far to sell his television shows, and that he was working to repay all investors when he was charged.

He acknowledged losing $380,000 at Las Vegas casinos but also said he put $700,000 borrowed against his house into his investments.

“I don’t deny making any of these transactions,” he told jurors. “But I definitely deny any criminal intent.”

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.