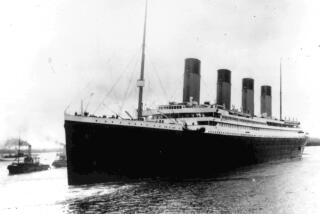

The Titanic Question: Would You Be a Hero or a Coward?

- Share via

Hero or coward?

After seeing “Titanic” last week, that was my No. 1 question. I pondered whether, given the circumstances in which Titanic passengers found themselves, I would have been courageous or craven at the moment of truth. Would I have helped people onto the dwindling supply of lifeboats, or would I have elbowed them aside and tried to save myself? Or, if too embarrassed to show blatant cowardice, would I have tried to finagle my way to safety?

I’ve found it best not to dwell too long on the subject.

It’s not that I know I’d have been a sniveling coward. In fact, I put the odds of that at no better than 50-50. It’s just that once a person starts contemplating the reality that faced the Titanic’s passengers, oh, the rationalizations one could make!

It’s one thing to know for sure that you’d put your loved ones on the last lifeboat ahead of yourself, but what about a stranger? What if the choice for the last seat was between me and a person in their 90s? What if the choice was between me (a heckuva nice guy) and someone I knew to be a scoundrel? What about the choice between me the replaceable scribe and a renowned surgeon?

When one of the only two available choices was death in the frigid North Atlantic, how far would I have gone to avoid it?

“Titanic” is the biggest movie of the holiday season and has generated much conversation about whether the love story is gripping enough and whether the special-effects sinking of the mock-up ship justifies writer/director James Cameron’s big budget.

Cinematic points to be debated, yes, but they seem puny when remembering that real people stood on the decks of the real ship and started doing the math as the clock struck 12 that night. Untold numbers of them probably made conscious decisions about whether they were going to be selfless or not. And it was not cocktail-party palaver--they knew the stakes were life or death.

How many of us would be heroic--and, to put an even finer point on it--without public acclaim? On the Titanic, whatever heroism occurred would have been the result of people making quiet, personal decisions to sacrifice themselves for others.

Sacrifice and heroism are among the most enduring human traits. I remember watching TV in January of 1982, with tears in my eyes, as videotape showed the man who dived into the icy Potomac River in Washington, D.C., to rescue a woman about to go down a third time after a plane crashed into a bridge.

Surprised that it made me weepy, I knew it had something to do with the sheer nobility of his deed. It was as pure an act as you could imagine: Seeing that the woman had let go of a rescue rope from a helicopter, the man, who was a passerby, peeled off his jacket and boots, swam 20 to 30 feet into the river and pulled her to safety.

We all like to think we’d come through, despite danger, but most of us never have to find out.

One night last July, 44-year-old Russell Coble of Capistrano Beach, who had also wondered over the years what he’d do in a pinch, got to find out.

With fire and smoke coming from his next-door neighbors’ home, Coble went into the living room and first pulled the semi-conscious elderly man from the couch. Then he tried to get to the bedroom, where the fire was centered and where he believed the man’s wife was trapped. Unable to enter the bedroom door from inside the house, Coble went outside and to a back entrance.

On what he thinks was his seventh attempt to get into the bedroom, he finally saw the woman and carried her to safety. I talked to Coble this week, mentioned my fixation about heroism aboard the Titanic and asked what he remembers about his own moment of truth.

“It was more reaction than anything else,” he said. “The only thought I really gave was how I could approach her room, what access there was. If I felt like my life was in danger, I wouldn’t have done it, but my thought also was that I wasn’t going to give up until I found her.”

Although he may not have felt he was risking his life, I suggested that the unforeseen could have happened and that, in point of fact, the woman was badly burned by the fire in her room.

“You always kind of wonder how you’d react,” he said. “I have a good feeling I did react in a positive manner. It would have been hard to live with myself, knowing I could have done something and didn’t.”

Now that he’s had some time to think about it, I asked if he reflects on it.

“Yeah, I do,” he said. “I think about it every so often. Until you get put in a situation like that--I hoped I’d react the way I did, but you don’t know until it happens.”

Coble also saw “Titanic” and, watching the passengers running around looking for alternate escape routes, he couldn’t help but be reminded of his nearly foiled rescue efforts.

I asked if he thought he’d have been heroic aboard the Titanic.

“I think I would have helped people, absolutely,” he said. “But like I say, you don’t know until you’re in that situation. But that’s my assumption of what I would have done.”

*

Dana Parsons’ column appears Wednesday, Friday and Sunday. Readers may reach Parsons by calling (714) 966-7821 or by writing to him at the Times Orange County Edition, 1375 Sunflower Ave., Costa Mesa, CA 92626, or by e-mail to [email protected]

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.