This Time, Allies Agree Iraq’s the Odd Man Out

- Share via

WASHINGTON — Saddam Hussein is challenging the international community yet again. But compared with last winter’s standoff, there’s a big difference: This time, it’s Iraq, not the United States, that is finding itself alone.

There are signs of greater unity between the United States and its key allies than at any time since the Persian Gulf War nearly eight years ago. There is a feeling that, as one French observer put it, “If something has changed here, it’s the perception of Saddam Hussein--he’s a fool.”

Dominique Moisi, deputy director of the French Institute of International Relations in Paris, added: “There’s a feeling the United States doesn’t have a clear military strategy, but there’s also a belief now that if we and the Russians are behind the Americans, maybe Saddam will take the threats more seriously.”

If airstrikes become imminent, that unity is certain to be tested. But on Sunday, political analysts on both sides of the Atlantic agreed that there is now a shared sense that only a clear threat of military action can force the Iraqi president to back down from his most recent refusal to cooperate with United Nations weapons inspectors.

“This is what is remarkable about the situation we’re in now,” said White House spokesman P. J. Crowley. “In contrast to crises in the past where various countries were willing to give Saddam Hussein the benefit of the doubt, in this case, there is no question that Saddam Hussein precipitated the situation we face now.”

Crowley spoke after President Clinton discussed the latest developments in Iraq with his senior foreign policy and national security advisors during a two-hour meeting at Camp David, 40 miles north of Washington. The meeting was part of a flurry of diplomatic activity over the weekend, and more such discussions are planned for this week in Washington, Europe and the Middle East.

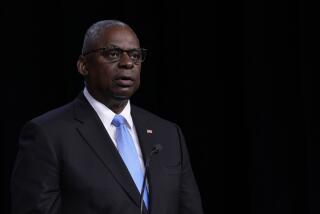

While none of those involved in Sunday’s meeting--including Secretary of State Madeleine Albright, Defense Secretary William S. Cohen and National Security Advisor Samuel R. “Sandy” Berger--were available for comment, Crowley said several options remained under consideration, including the use of force.

“The president made no decision. There is more work to be done,” Crowley said.

Another White House official said Clinton was expected to discuss the crisis with several world leaders by telephone this week.

The U.N. inspectors, who operate under the terms of the 1991 Gulf War cease-fire, are searching for evidence that Iraq either possesses nuclear, biological or chemical weapons or has the ability to produce them. Hussein triggered the latest crisis nine days ago by issuing a blanket refusal to cooperate further with the inspectors.

Reactions in recent days, especially in capitals such as Paris and Moscow, where governments worked feverishly to head off U.S. airstrikes against Hussein in February, indicate that sympathy for the Iraqi leader has dwindled sharply during the intervening months and that he may have seriously misjudged the strength of his position.

“France, as the entire [United Nations] Security Council, has a position of great firmness, which . . . is shared by the whole international community,” French President Jacques Chirac said in Paris on Saturday prior to a meeting on Iraq there between Berger and his British and French counterparts.

Last winter, trips by senior French and Russian diplomats to Baghdad eventually produced an agreement between Hussein and U.N. Secretary-General Kofi Annan on terms for resuming U.N. weapons inspections, but the frantic diplomacy projected an image of their trying to shield the Iraqi leader from threatened American airstrikes.

Those events injected a degree of bitterness into U.S. ties with France and Russia and opened the Clinton administration to accusations from critics at home that it had neglected the coalition of countries that joined to defeat Hussein in the Gulf War.

In France on Sunday, however, political analysts sketched a mood of reluctant acceptance that now, force may be the only action Hussein understands.

And in Britain, one of the few European allies that backed the U.S. threat of force in February, the latest crisis seems to have only hardened the position of Prime Minister Tony Blair’s government.

“We’re as convinced now as ever that the only message Saddam Hussein ever understands is diplomacy backed by a determined threat to use force,” a Downing Street official said.

British Defense Secretary George Robertson was scheduled to depart for the Middle East on Sunday to consult with Arab allies, in part to reinforce a hard line set down last week when Cohen traveled to the region.

Among Arab states too, support for Iraq is markedly diminished from what it was last winter. In an interview Sunday with the French news service Agence France-Presse, Saudi Foreign Minister Prince Saud al Faisal said Hussein is “fully responsible” for the current standoff.

While Saud said his country would prefer a diplomatic solution to the crisis, he did not rule out support for a military option. “For the moment, we are not solely discussing the military option but all options,” he told the news service.

Iraq is also expected to top the agenda at a meeting of European Union foreign ministers today in Brussels.

A senior State Department official said that the closer cooperation from allies stems, at least in part, from a low-key response by the Clinton administration last summer when Hussein unilaterally restricted inspectors’ movements. That episode, followed now by Hussein’s decision to end cooperation, showed allies that only the threat of tough measures can work to contain him, the official said.

While noting the new solidarity among America’s allies, analysts Sunday questioned to what extent this support would hold if the United States actually went through with airstrikes. The U.S. has more than a dozen combat ships and 170 military aircraft in the Persian Gulf region.

The strength of the anti-Hussein reaction buoyed senior administration officials as Clinton met Sunday with his national security team, although these officials stressed that the United States would still prefer to resolve the crisis peacefully with unconditional freedom of movement for the U.N. weapons inspectors, known formally as the U.N. Special Commission, or UNSCOM, and personnel from the International Atomic Energy Agency.

“This whole thing is about getting UNSCOM and the IAEA back in. That’s what the current consultations are all about,” said another White House spokesman, David Leavy.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.