Driven by a Son’s Sacrifice

- Share via

WINFIELD, Ala. — The CIA man was being brought to a funeral home near Arlington National Cemetery, so the distraught father shuttered his realty office in this three-stoplight town and flew up to the nation’s capital.

Running through his mind, he would say later, was Mike’s admonition, “Daddy, don’t ever believe I’m dead till you see my body.”

There in the casket lay Mike, and the father reached in and ran his hands across his son’s forehead. He remembered pulling up Mike’s head and peering at the back of his skull. He saw what appeared to be two exit wounds. He felt along his arms and legs and found bruising. It looked to him as if death came with a shot to each temple.

“I wanted to know: How did he die? Was he broken up? Was he tortured?” the father recalled.

More than three years have passed since Johnny “Mike” Spann, a CIA operative working in Afghanistan, became the first U.S. combat fatality in the war on terrorism. In that time, his father, Johnny Spann, a small-town real estate agent unversed in the ways of Washington and foreign intrigue, has undertaken an international odyssey to learn how his son died, to quell rumors and maybe to hold someone responsible for the death.

Mike Spann, a member of the CIA’s paramilitary Special Activities Division, was among those dispatched to Afghanistan in the weeks following the Sept. 11 attacks to track down Osama bin Laden. He was shot to death during an uprising by Taliban prisoners on Nov. 28, 2001, near Mazar-i-Sharif.

But the father needed to know more about what happened to his son that day. He has lobbied the Department of Justice, the Pentagon and the CIA. He has questioned Special Forces soldiers who were in Afghanistan when his son died. He has met with then-CIA Director George J. Tenet. And he has traveled to Afghanistan to interview some of the people who last saw his son alive.

At a campsite in the desert, the 56-year-old father broke bread with once-feared Afghan warlord Abdul Rashid Dostum, whose Northern Alliance soldiers worked with the CIA in the early days of the U.S. incursion into Afghanistan and were on the scene when the 32-year-old American was killed.

He persuaded Dostum to give him a videotape of the activity at the courtyard leading up to his son’s death. Securing the tape was a major victory for Johnny Spann, and it has spurred him to keep digging.

*

Three generations of Spanns have lived in Winfield, a town of about 4,700 northwest of Birmingham. Mike’s grandfather worked in the cotton mill, and his father was born here. Mike went to Winfield High, graduated from Auburn University and joined the Marines.

Today there is a memorial to Mike next to town hall. They named one of the main thoroughfares after him too. His father’s office is virtually a shrine to him, complete with his boyhood baseball cap, displayed on a shelf behind the desk. Someday the hat will be a gift for Mike’s son, now 3.

Mike is also known well beyond Winfield. For some, his standing as the first American to die in combat after the Sept. 11 attacks makes him a symbol of the struggle against terrorism.

In the courtyard where he died, the new Afghan government erected its own memorial to Mike.

Recently, his father received an e-mail from an American soldier who had visited the site.

“I felt a great admiration for this man I had never met,” wrote Army Staff Sgt. Jim McCool. “Even after having been there several times, I still get this feeling of great importance about this place. It’s like a ‘walking in the footsteps of a legend’ kind of a feeling.”

Mike’s father wants to preserve that image, even to the point where CIA and other government officials have cautioned him about becoming obsessed with how Mike met his end.

“I’ve been told that none of this matters any more,” Spann said. “I was told that things happened, and that Mike was dead now and that it didn’t matter any more. But everything matters to me.”

At home, he often plays the Dostum video on the living room TV, next to the U.S. flag that covered his son’s casket. He often slows and rewinds the tape at crucial scenes.

*

By the time terrorists hit New York and suburban Washington, Mike had already left the Marine Corps for the CIA. He was a father of three. Yet after the devastation at the World Trade Center and the Pentagon, he volunteered to go to Afghanistan and search for Bin Laden.

“There was no way he wasn’t going to go,” his father said.

Accompanied by other CIA operatives and Special Forces soldiers, Mike joined with Northern Alliance troops in late November 2001 for their siege of Mazar-i-Sharif. Several hundred Taliban prisoners were taken and herded into the “Pink House,” a low-slung fort in nearby Qala-i-Jangi.

Among the prisoners, it was later learned, was John Walker Lindh, a young Northern California man who had traveled to the Middle East on a religious odyssey and ended up with the Taliban.

On Nov. 25, Mike went to the Pink House hoping to find captives with information about Bin Laden. Late that morning, the prisoners revolted.

It would be several days later that CIA officials visited Winfield to tell Spann that his son had been killed in the uprising while “fighting hand-to-hand.”

Mike’s death made headlines. His father remembers watching news video that showed Mike questioning a young American less than two hours before the uprising.

The man was soon identified as Lindh, who was dubbed the “American Talib” and taken into U.S. custody.

Almost immediately, Mike’s father suspected that Lindh had something to do with his son’s death.

Spann feared the CIA would never divulge the full story. He recalled Mike’s warning to believe nothing until “you see my body.” He pressed the CIA for the autopsy report, but it took a personal visit with Tenet to obtain a copy. He found the military doctor in Germany who had examined Mike’s body. He lobbied for photographs.

Other than confirming that the younger Spann suffered two gunshots to the head, the evidence was neither consistent nor conclusive. He could not tell whether Mike was shot from above or at close range.

He did not know whether Mike had been tortured or executed in cold blood, or neither or both.

He arranged a visit with Special Forces soldiers in Norfolk, Va., who told him Mike had gone down firing his AK-47, and when the rifle emptied, he turned his 9-millimeter pistol on the rioters rushing in and out of the Pink House.

As Spann conducted his investigation, Lindh was being prosecuted in the U.S. courthouse in Alexandria, Va. He was facing a possible life sentence for taking up arms with the Taliban. In Lindh, Spann found someone to hold responsible for his son’s death.

Spann theorized that the prisoner revolt was carefully planned and that Lindh was aware of it but failed to warn Mike, a fellow American.

Spann became a fixture at the courthouse, demanding justice. At one point, Lindh’s father, Frank, approached him at the close of a pretrial hearing and said something to the effect of “John had nothing to do with Mike’s death.”

Spann bristled and walked away.

“I should have taken out some of my revenge on him,” he recalled.

George C. Harris, one of Lindh’s attorneys, said Frank “was just trying to reach out his hand and be friendly.”

Then the two sides agreed to a 20-year plea deal for Lindh. Spann said he learned of it during a cellphone call in the drive-through lane at the McDonald’s in Winfield. He had to pull over to calm down.

Spann was convinced the Justice Department had caved in rather than allow U.S. intelligence officers or enemy combatants to testify at a trial, something they have blocked in numerous Sept. 11-related cases.

Federal prosecutors in the Lindh case denied such assertions, saying 20 years was an appropriate sentence.

At his sentencing, Lindh stated that he “had no role” in Mike’s death.

Spann spoke too, for about 18 minutes, telling the judge of the autopsy report and the trajectory of the bullets.

He suggested that Mike had been shoved to his knees and executed, close to where Lindh would have been.

In late 2002, several months after the case was settled, Spann attended the dedication of the Afghan government’s marble memorial to his son. While there, he interviewed two doctors who said they were standing with Mike when the riot broke out and that he had tried to fight back. Spann found a Northern Alliance soldier who said prisoners discussed what to do with Mike’s body and agreed that it meant a “sure trip to heaven” for whoever had killed him.

He met Dostum, now the Afghan government’s chief of staff for military affairs. The former warlord once allegedly sealed hundreds of Taliban captives in transport containers until they suffocated.

Over an evening meal of chicken and fruit at a campground, Spann said Dostum politely thanked him for Mike’s sacrifice. Spann, who had heard of a videotape of the events that day in the courtyard, said he asked Dostum about it.

The general initially denied it existed but eventually turned it over. For Spann, that was a breakthrough. The video, believed to have been recorded by a Northern Alliance commander, covered the two hours leading up to the riot.

Mike’s father, along with much of the nation, had seen some of the footage before, when a seven-minute version was aired on television.

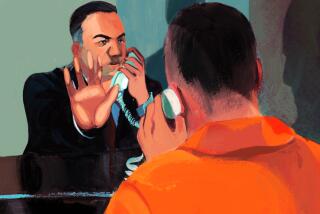

In that portion, a handcuffed Lindh is escorted out of the house and onto his knees in the dirt courtyard and repeatedly refuses to respond to questions from Spann and another CIA operative, Dave Tyson.

Much of the rest of the tape shows several hundred cuffed prisoners being marched out of the Pink House and forced to sit on the ground in rows. Mike can be seen in the background, in blue jeans and a blue pullover sweater, an AK-47 slung over his back.

The tape convinced Spann that the prisoners plotted the uprising the night before. He believes they waited until half were out in the courtyard, giving them better position. He is certain that Lindh must have known what was about to happen.

But Harris, Lindh’s defense lawyer, denied that his client knew about the riot. He said it was hatched by a small group of Uzbek prisoners and that Lindh did not understand their language.

Harris also noted that Mike never identified himself to Lindh as a U.S. official, which appears to be true from the tape, and that Lindh assumed Mike was working with Dostum, which was correct because the U.S. was aligned with the Northern Alliance.

“That was John’s greatest fear, of being in Dostum’s custody and knowing how he treated prisoners,” Harris said. “Being in Dostum’s custody seemed to be sure death.”

The last two minutes of the tape show Mike behind the doctors, away from the Pink House. When the riot’s first grenade goes off, the tape abruptly stops. The video does not show what happened to Mike.

Harris said Lindh, hands still cuffed, was shot in the leg. Dozens of prisoners were killed, but about 80, including the wounded Lindh, returned to the Pink House for cover until they were routed by Dostum’s troops three days later. Lindh was turned over to U.S. forces.

Although the tape does not implicate Lindh in Mike’s death, it appears to counter recent allegations by Taliban soldiers now held at the U.S. prison in Guantanamo Bay, Cuba, who claim that Mike sparked the riot when he killed one of the prisoners in the courtyard.

Those allegations are contained in FBI documents obtained through a lawsuit by the American Civil Liberties Union of New York aimed at documenting prisoner abuse by the U.S. military.

Spann says the video shows the prisoners are lying, but he is not sure how much of the public believes him -- especially in light of the outrage over prisoner torture and abuse in Afghanistan and Iraq.

So Johnny Spann continues his quest. He is working behind the scenes to quash an effort by the imprisoned Lindh for a presidential commutation of his sentence and says he is thinking of talking to Yaser Hamdi, another American citizen captured at the Pink House with Lindh.

Hamdi has since been returned to his family in Saudi Arabia, and Spann says he is looking into another trip to that part of the world.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.