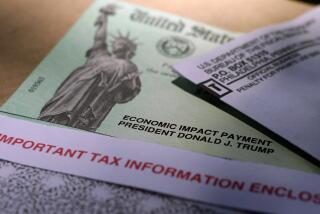

Fake money a growing problem for small businesses

- Share via

Funny money is no joke for small-business owners.

Counterfeit cash cuts into profits at firms, many of which are already struggling in the tight economy, and puts pressure on prices.

The fake bills can be hard to spot with an untrained eye, and sophisticated digital printers have made it easier for criminals to create higher-quality bad bills, faster. And the problem appears to be growing.

The Secret Service, which is in charge of investigating and preventing counterfeiting, said it helped remove from circulation more than $182 million in fake U.S. currency in the fiscal year that ended Sept. 30, 2009. That’s more than double the amount in fiscal 2008.

Cash-based businesses such as gas stations, liquor stores, fast-food restaurants, convenience stores and mom-and-pop grocery stores are obvious targets.

A typical scenario at a local small business: A motorist in a hurry pops into the Union 76 station on Lake Avenue in Pasadena and tosses a $20 bill at manager Valod Mehrabian. The driver barks, “Twenty on No. 5,” and dashes out to gas up.

The industry veteran says he feels the bill to check for the characteristic heft of a real bill. If it doesn’t pass muster, he runs it through a small machine that shines ultraviolet light on it.

Real bills have a thin strip of fluorescent polyester thread woven in that, under UV light, glows a different color for each denomination and contains printing revealing the value of the bill. The strip in a $20 bill glows green.

If it’s a fake — and $20 bills are the most commonly counterfeited bills in the U.S. — Mehrabian tells the customer, gives it back and asks the customer to leave.

“Their first reaction is objection. ‘No, no, no! It’s good,’ they’ll say,” Mehrabian said.

Debbie King said she can almost always tell when a criminal is trying to pass a bad bill at her family business, Commercial Tire Co., which has locations in Vernon and in Bloomington in San Bernardino County.

“They start pacing around, and they start sweating because we are holding things up,” King said. Employees at the business, which is owned by her father, are supposed to use a UV machine to check bills. Some, though, balk because they worry they will offend customers.

More often, it is an untrained or uncaring cashier who accepts the bills at a small business, experts said.

Criminals try to get around authorities in several ways. Experts say bills printed on unofficial paper can be coated with hairspray that can fool special pens meant to detect legitimate currency paper.

Higher denomination fakes often are printed on real, lower-value bills that have been bleached clean of ink, said Jim Smith, senior vice president of sales and marketing at UVeritech Inc., a Glendora company that makes and sells fraud prevention products.

Just last month, authorities in San Diego broke up what they called “one of the most organized counterfeiting operations” ever discovered in the county, which they said passed more then $100,000 worth of fake $100 bills at local businesses. The fakes started out as real $1 bills.

Small businesses in the Florence-Firestone neighborhood of South Los Angeles have seen even smaller bills being faked, said Efren Martinez, executive director of the Florence-Firestone Chamber of Commerce.

“It’s gotten to the point where they are counterfeiting the ones and the fives,” said the executive, who organized a workshop with a major bank and the local sheriff’s station to teach small merchants how to spot bad bills. “Normally business owners don’t check those.”

Small businesses can fight back by teaching employees how to spot bogus bills: Posters and other resources are online at https://www.newmoney.gov. Countertop UV machines can cost $100 or less. Some machines can also detect micro-printing, watermark and magnetic security features. Hand-held UV pens are even less expensive.

To keep ahead of counterfeiters, the federal government in April unveiled a new design for the $100 bill, the most counterfeited U.S. note abroad, with even more sophisticated color-shifting ink and plastic strips with 3-D images. The new bills are due out next February.

More to Read

Inside the business of entertainment

The Wide Shot brings you news, analysis and insights on everything from streaming wars to production — and what it all means for the future.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.