Understanding Dzhokhar Tsarnaev via Masha Gessen’s ‘The Brothers’

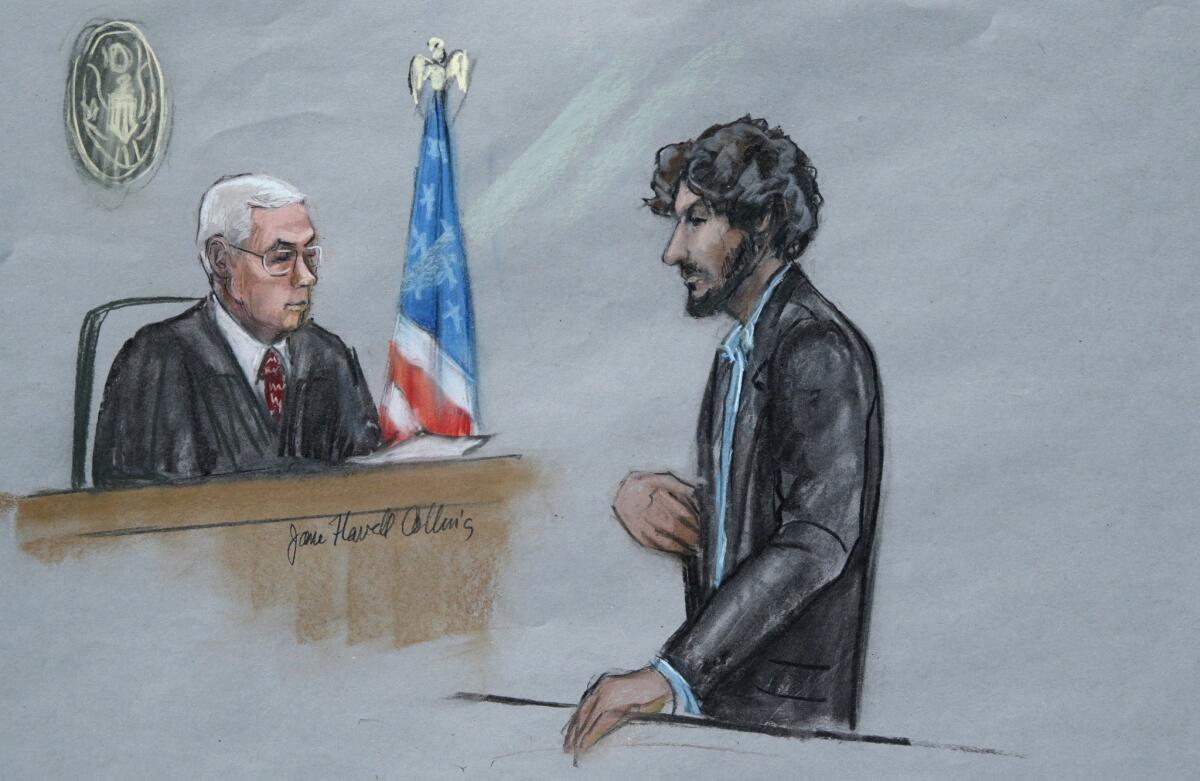

In this courtroom sketch, Boston Marathon bomber Dzhokhar Tsarnaev, right, stands before U.S. District Judge George O’Toole Jr. as he addresses the court during his sentencing.

- Share via

During high school in Cambridge, “Dzhokhar had continued to make good grades and good friends and make everyone happy. ... He was also both smoking and dealing weed, but he was such a perfect mirror of everyone’s best expectations that even the most experienced Rindge teachers saw none of the usual signs: his clothes were purposefully messy, not stoner-messy; his big brown eyes appeared focused, if only ever for the minute or two it took to have a meaningful interaction with any of them in the school’s vast hallway.” That’s from the book “The Brothers” by Masha Gessen, released in April.

Gessen, a Russian American journalist, reported extensively on the Tsarnaev family’s history in Chechnya and how it affected sons Tamerlan and Dzhokhar, and what happened after the brothers set two pressure-cooker bombs to go off at the finish line of the Boston Marathon in 2013. During the attack, three people were killed and 260 injured; elder brother Tamerlan was killed during the manhunt for the Tsarnaevs.

On Wednesday, Judge George O’Toole Jr. formally sentenced Dzhokhar Tsarnaev to six death sentences and 10 terms of life in prison without parole.

The judge quoted Shakespeare: “The evil that men do lives after them. The good is often interred with their bones,” adding, “so it will be for Dzhokhar Tsarnaev.”

In Gessen’s book, she argues that the Tsarnaev brothers’ story “remains a small story, in which nothing extraordinary happens — or, rather, no extraordinary event is necessary to explain what happened. One had only to be born in the wrong place at the wrong time, as many people are, to never feel that one belongs, to see every opportunity, even those that seem within reach, pass one by — until the opportunity to be somebody finally, almost accidentally, presents itself.”

Book critic David Ulin observes, “This is not a popular perspective; it asks us to wrestle with ambiguities that we might prefer to leave alone. But it also deepens the tragedy of the bombing by framing its perpetrators not as monsters but as human beings.”

More than 30 victims spoke out at Wednesday’s court hearing, detailing their own anguish and lives drastically changed by the attack. “The choices that you made are despicable,” said Patricia Campbell, whose daughter Krystle was killed at the marathon. Jennifer Rogers, the sister of MIT police officer Sean Collier shot days later, said, “I will never have a complete family again.”

Tsarnaev spoke publicly about the bombings for the first time before his sentence was read. “I am sorry for the lives I have taken, for the suffering I caused, for the damage I have done — the irreparable damage,” he said.

Gessen’s book “The Brothers” looks at the history of dislocation of ethnic Chechens by Soviet authorities and how that affected the immigrant Muslim family, which arrived in the U.S. not long after 9-11.

“Gessen deftly relates that war on terror mindset to what the Tsarnaevs experienced in Russia, where a series of bombings in 1999 ratcheted up anti-Chechen sentiment,” Ulin wrote in our review. “For the Tsarnaevs — a Muslim family from a war-torn republic — the timing was [Gessen writes] ‘as bad as it had ever been: they landed in America precisely at the moment when they and their kind were seen as most suspect.’ ”

In court Wednesday, Tsarnaev said, “I also asked Allah to have mercy upon me and my brother and my family, and I pray to Allah to bestow his mercy upon victims and their families.”

Book news and more: I’m @paperhaus on Twitter

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.