After 18 years in prison, he took over his old L.A. gang. A string of murders followed

- Share via

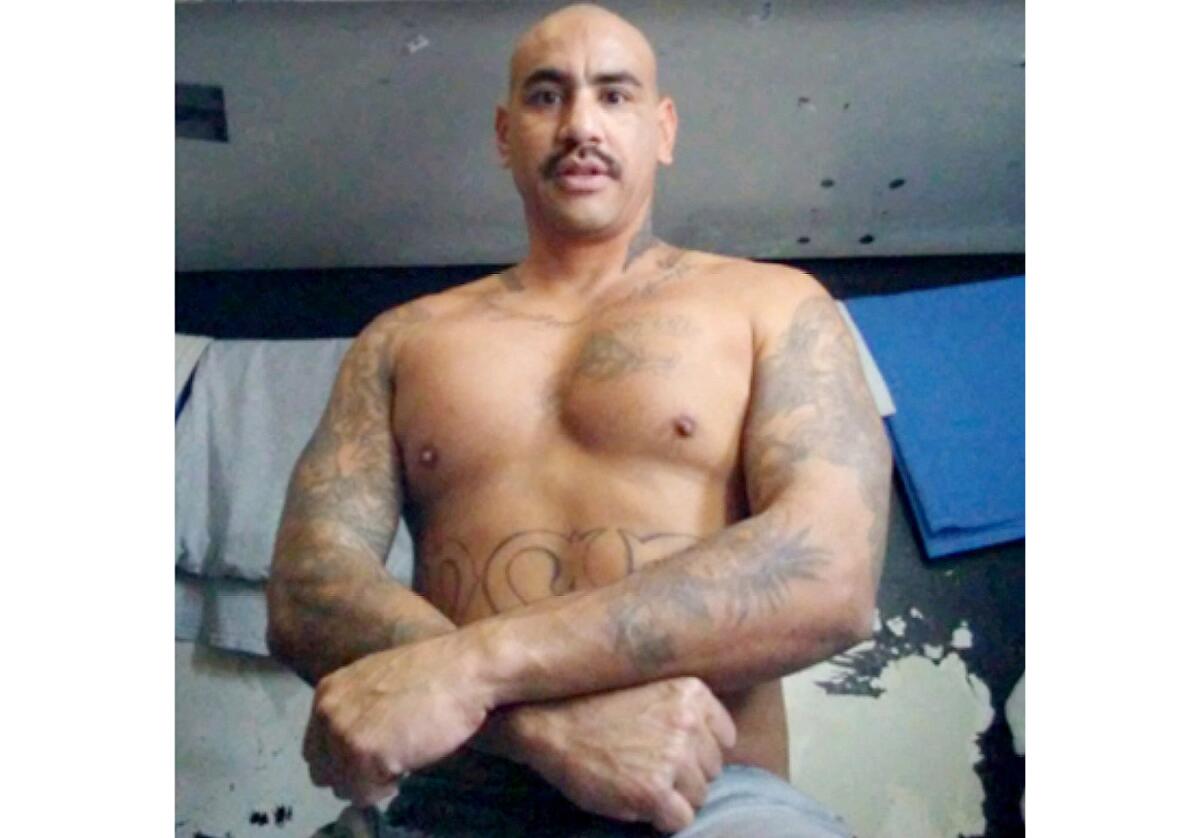

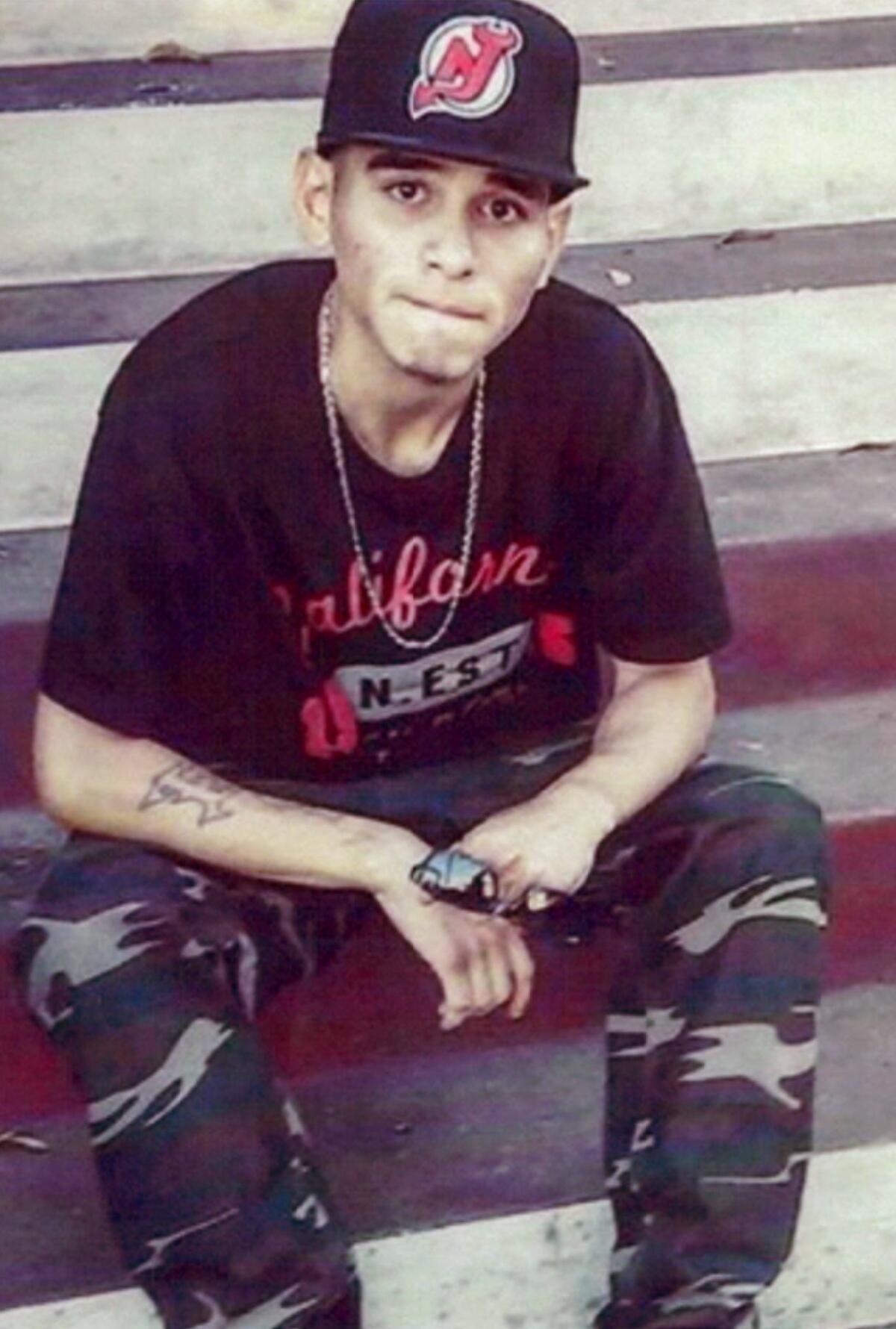

Ezequiel Romo had been gone a long time.

He went to prison in 1996. When he returned to Panorama City 18 years later, he didn’t like what he saw.

He was going to “clean out house,” Romo told another veteran of his gang. He would rid the neighborhood of rivals, of informants, of drug addicts and the do-nothings he considered dead weight.

Prosecutors said the 45-year-old made good on that promise: On Romo’s orders, members of his gang, Blythe Street, turned on and killed one another in a string of murders that left eight dead, according to evidence presented at a months-long trial that began in March in Los Angeles Superior Court.

Romo used Blythe Street to raise his own standing within the Mexican Mafia, the prison-based syndicate whose ranks he hoped to join, witnesses testified. He put members of his gang to work selling the Mexican Mafia’s drugs, collecting their debts and eliminating their enemies. Anyone who didn’t go along, prosecutors said, was eliminated.

Testimony and Romo’s text messages created the portrait of a micromanager who knew just one response to petty slights and suspicions. Get an unsanctioned tattoo? “Take care of it,” Romo told his lieutenant. When the lieutenant, who dutifully orchestrated that murder and several more, got strung out and stopped returning Romo’s calls, it was his turn to go.

And if you had something Romo wanted, like a kilogram of cocaine, why pay for it? His dealer got the same treatment: a bullet in the back.

“Why would you kill your own gang members?” Deputy Dist. Atty. Eric Siddall asked in his closing argument. “Because in Romo’s world, if you don’t fit the mold, if you don’t do what he wants, you get killed.”

‘All I ask for is complete control’

Blythe Street takes its name from a few blocks between Van Nuys Boulevard and Brimfield Avenue in Panorama City. Successions of police task forces and anti-gang programs have never managed to shake its reputation as a drug market or weaken the gang’s pull on generations of children who grow up in the apartment complexes that crowd one another behind tall metal fences.

Members of Blythe Street tend to use the same word to describe the gang: “You feel like it’s family,” a former gang member told The Times, speaking on the condition of anonymity.

Subscribers get exclusive access to this story

We’re offering L.A. Times subscribers special access to our best journalism. Thank you for your support.

Explore more Subscriber Exclusive content.

Some were 12 or 13 when they joined, their parents absent or uninterested in their lives. They’d spend their days finding “ways to survive,” the gang member said. “Nobody has a job. Nobody has monthly income. So you’re robbing people, jacking cars, selling drugs.”

On any night you’d catch them hanging out in apartment complexes with names such as the Casitas, the Pinks and Green Village. They’d lock themselves inside the laundry rooms to smoke methamphetamine, squat in vacant apartments, sell drugs in the parking lots.

If a carload of rivals from gangs such as Columbus Street or Barrio Van Nuys pulled up, members of Blythe Street vanished into the warren of hallways and stairwells. The night air crackled with the anticipation that gunfire might erupt from any oncoming car.

This was Romo’s domain: the street, the gang, the money to be wrung from the pushers and dispensaries and gambling parlors that operated within the gang’s territory. “All I ask for is complete control of Panorama City,” he wrote in 2017 in a WhatsApp message from prison to an underling on the streets.

Five feet 11 and well-built, Romo wore glasses and a rumpled charcoal suit in the courtroom. The collars of his dress shirts could not entirely hide the hummingbird and butterfly tattooed on either side of his neck.

Unlike his three younger co-defendants, who seemed by turns bored and mildly amused by the proceedings, Romo watched the testimony intently, taking notes on a legal pad and whispering often in his lawyer’s ear.

Romo, whose parents divorced when he was 4, was raised mostly by his paternal grandparents in San Fernando, according to court documents. As a teenager, he supported his grandparents by working for his uncles, who owned a construction business and machine shop.

Romo was 18 when he got in a fight with another teenager, Manuel Avila, at a Tommy’s hamburger stand on Roscoe Boulevard. After Avila punched him in the face, Romo shot the 19-year-old in front of a crowd of diners, The Times reported. It was 1995.

“He was just beginning his life,” Avila’s sister told the judge before Romo was sentenced in 1996 for manslaughter, according to a transcript of the hearing. “He was doing so good in school. He had so many goals and everything in life. His life just stopped there.”

She urged the judge to imprison Romo for as long as the law allowed. “He’s going to be hurting our community,” she said.

But Romo’s lawyer, producing letters from his client’s family, neighbors and a former teacher, pleaded with the judge not to write the young man off. “I think that he’s worth saving, judge. That’s all I can say.”

Sentenced to 10 years for the manslaughter, Romo would do 18 after being convicted in 2007 of assaulting another inmate, records show.

When he got out in late 2014, Romo met with another veteran of Blythe Street, who testified at his trial in hopes of reducing a sentence for drug trafficking. The man, identified in the court record as Witness 1 for his safety, said Romo told him “his whole agenda, what he was representing.”

In prison, Romo had worked under the Mexican Mafia. Blythe Street never had much to do with the group, whose members were locked up in distant penitentiaries, Witness 1 said. The extent of their involvement was paying “taxes,” a few hundred dollars a month, which Blythe Street came up with by extorting Mexican nationals who sold crack and heroin in Panorama City.

“When I was a kid, it was about neighborhood. It was about Blythe Street. We didn’t have much to do with politics,” Witness 1 said, referring to the Mexican Mafia.

Romo envisioned something different, Witness 1 said. The Mexican Mafia needed feet on the ground to realize schemes hatched from prison. Working for three Mexican Mafia members — Frank “Playboy” Fernandez, Raul “Huero Smooth” Garcia and Jose “Cartune” Loza — Blythe Street collected debts, moved drugs and muscled those who needed persuading, Witness 1 testified.

“His thing was making things right for them people. Doing favors for them. Taking care of people in the county [jail]. It sounded good,” Witness 1 testified, “but a lot of violence came after.”

First, Romo needed to get his own house in order. He intended to purge the gang of “dirty homeboys” — informants, addicts and dissenters, Witness 1 said.

Blythe Street members started turning up dead around 2015. Rumors flew that they had not been killed by rivals, said the gang member who spoke to The Times. No one went looking for revenge or tattooed the names of the dead on their bodies. The funerals — and the car washes put on to fund them — were sparsely attended.

“I should have seen it was a red flag,” the gang member said.

A kilo of cocaine, a ‘setup’

In a gray apartment complex off Blythe Street, a dealer called Chaparro — Shorty — rented three units: one for his family, one for a girlfriend and one “where he cooked his dope,” Witness 1 testified. Chaparro paid Romo every month for the privilege of selling in the gang’s territory, he said.

After a drug bust, Chaparro fled to Mexico. Romo arranged to buy a kilogram of cocaine from Chaparro’s supplier, a Mexican national whom Witness 1 knew only as “the paisa.” His name was Felipe Delgado.

Romo took the cocaine, promising to return with the money in a week, Witness 1 testified. Then Romo started spreading word that Delgado was an informant, according to Witness 1, who doubted the story. Romo “wanted to kill him because supposedly he was a rat, but at the same time he had taken a kilo of cocaine. And he had kept that money. He had no intention of paying.”

Because Romo was on parole, he had a GPS monitor on his ankle. So he and Witness 1 arranged for a young member of Blythe Street, Steven “Youngster” Mendoza, to murder Delgado. The plan was for Romo to meet Delgado behind Chaparro’s apartment complex. Romo would announce he was getting the money. Mendoza would wait until Romo had walked out of sight before stepping out from behind a car and shooting Delgado.

Romo believed his GPS monitor would show that he was in front of the building while Delgado was killed behind it, giving him an alibi, Witness 1 testified. To establish one of his own, Witness 1 went to his son’s football game at Panorama High School.

At 5:30 p.m. on Nov. 6, 2015, Delgado was shot three times in the back behind Chaparro’s apartment complex. Witness 1 saw the police helicopter fly over the football stadium. He knew where it was headed.

Mendoza was charged in the same case as Romo but has yet to go to trial. Mendoza has pleaded not guilty to murdering Delgado.

Two months after Delgado’s death, Romo was arrested with half a kilogram of methamphetamine in his car, court records show. He pleaded guilty and was shipped off to the Imperial County desert to serve a four-year term at Centinela State Prison, which would become the “corporate headquarters” for Blythe Street, said Siddall, the deputy district attorney.

There, Romo had access to cellphones smuggled in by prison staff or dropped inside the walls using drones, testified Sgt. Craig Parkhill, an investigator at Centinela.

Witness 1 said he kept Romo updated on the neighborhood, including the matter of Isidro “Topo” Alba.

Once a leader of Blythe Street, Alba, 38, was by then living out of his car, scratching out a living by peddling methamphetamine and shaking down other dealers. He said he was collecting the money on behalf of Mexican Mafia members in federal prison, but Witness 1 doubted it — especially when it emerged that one of the men Alba claimed to be working for was dead.

Romo had warned Alba to stay out of Panorama City, but after he returned to prison, Witness 1 got word that Alba was coming around again. A liquor store owner was complaining of being extorted.

Romo told Witness 1 to let Alba know there was a way to redeem himself: Loza, one of the Mexican Mafia members aligned with Romo, was facing trial on charges of gunning down another member, Dominick “Solo” Gonzalez. Alba had claimed to work for Gonzalez.

To bolster Loza’s claim of self-defense, Romo wanted Alba to testify Gonzalez was violent, Witness 1 said. He recalled that Alba refused to “jump in the hot chair,” saying, “That sounds more like telling.”

The night of Aug. 27, 2017, Alba was waiting outside a Target in Van Nuys for a customer who wanted to trade a phone for methamphetamine.

Sitting beside him in his Dodge Avenger, Alba’s girlfriend — whom The Times is not naming for her safety — noticed a black sedan drive past several times.

Alba hesitated. “Do you think this is a setup?” he asked.

“Just hurry the f— up,” she told him, handing him the drugs from the glove box.

Alba got out. The next thing she heard were shots. She saw Alba running back to the car, chased by two men in hooded sweatshirts. She identified them as Juan “Flaco” Ramirez and Yordin “Little Goofy” Enere, both members of Blythe Street.

Ramirez, whom she had known for years, was standing outside her window when he opened fire at point-blank range, she testified.

When the gunfire stopped and the shooters had fled, she ran into the street, raising both hands to flag down an oncoming car, according to a video played in court. Too late, she recognized the black sedan.

Ramirez and Enere stepped out, along with a third man, and shot at her again, she testified. She ran back to the car, laid down in the seat and played dead.

When police arrived, they found her bleeding from the shattered glass of her window. Somehow, none of the seven bullets fired through it had hit her.

Alba was dead. He never had a chance to grab the .38 from the glove box.

Enere and Ramirez have pleaded not guilty to murdering Alba and attempting to murder his girlfriend. They have yet to go to trial.

‘This is not a game’

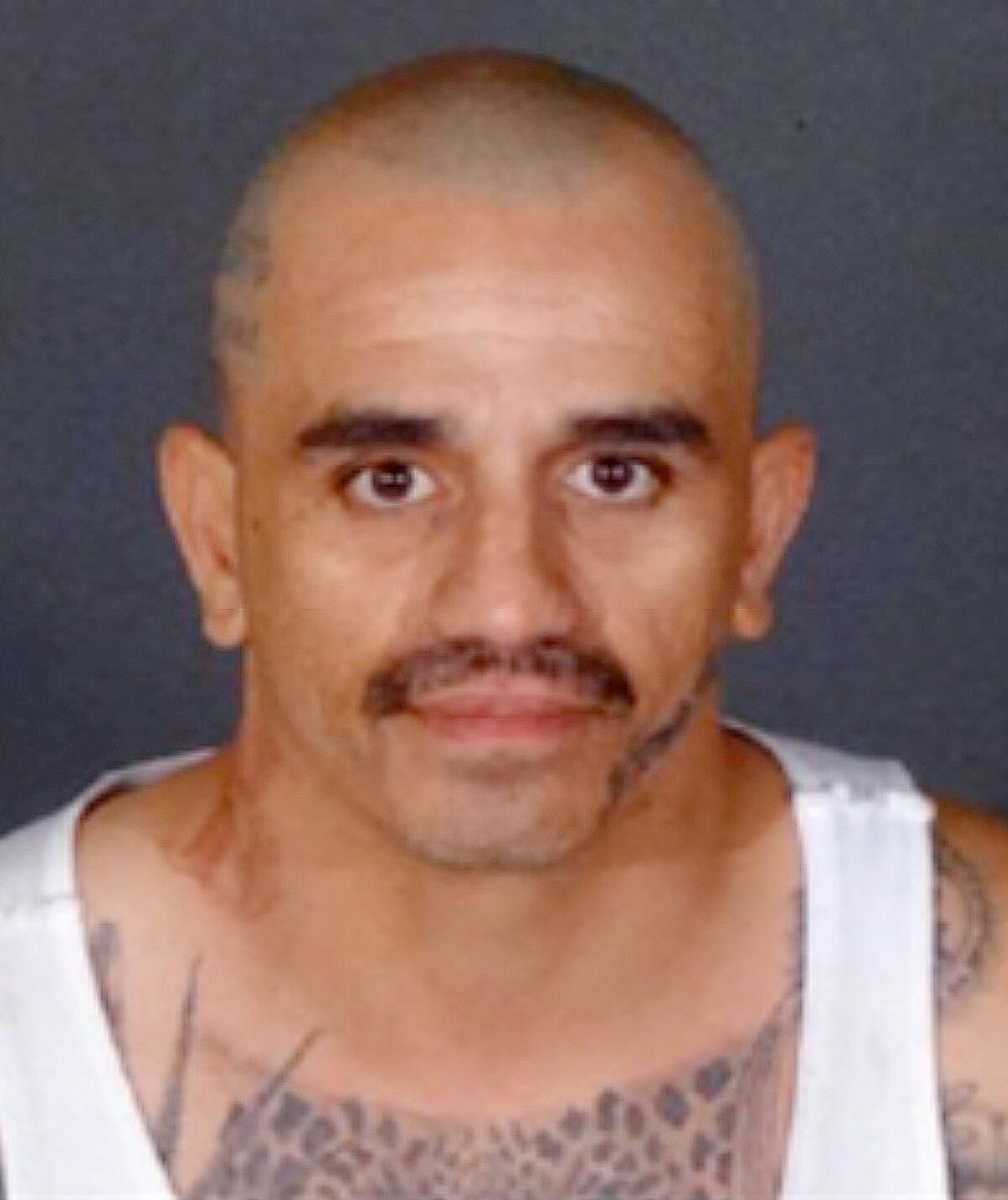

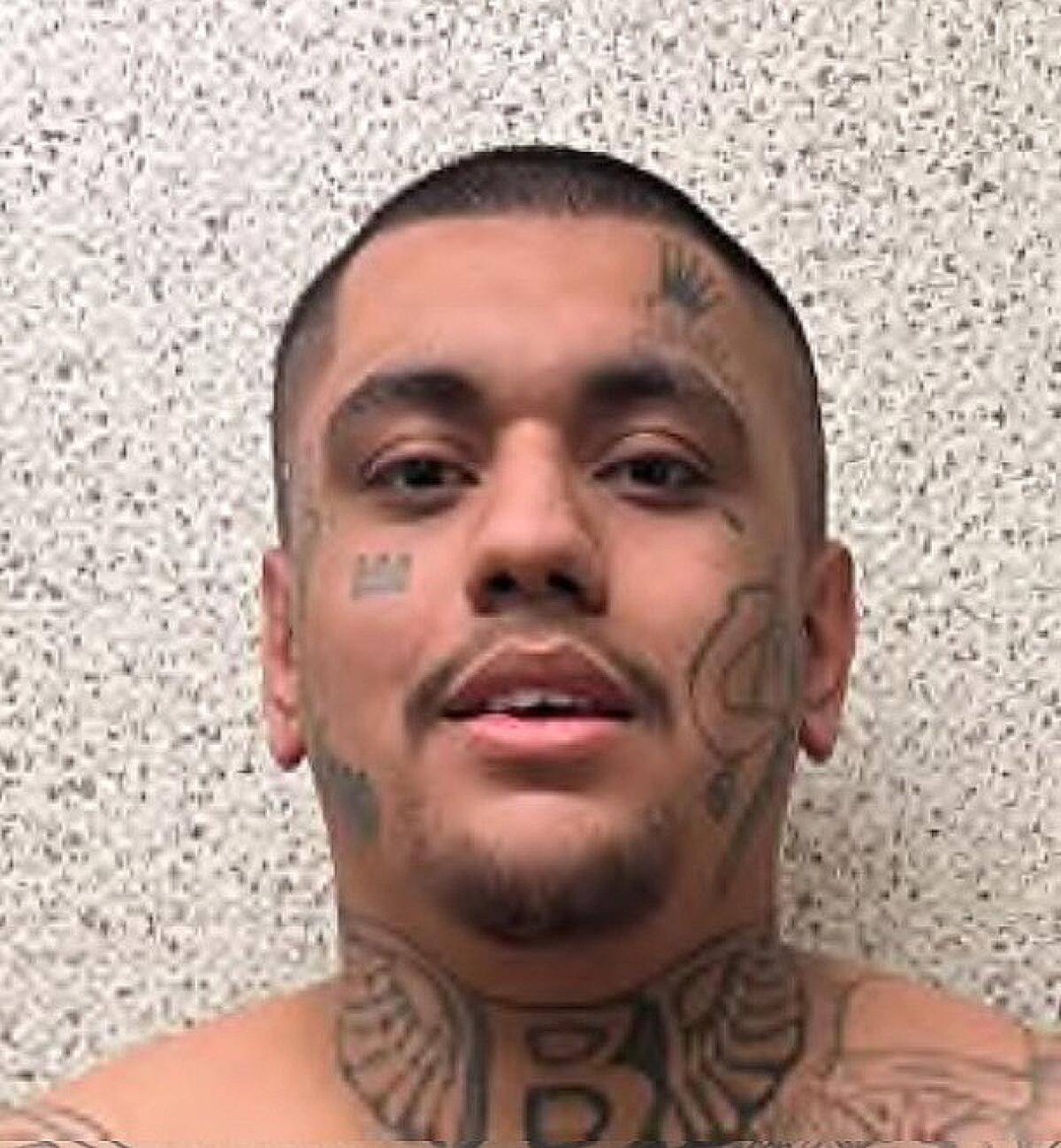

Another man was in the black sedan that night. His name was Oscar Molina.

After Romo returned to prison, Molina, a stocky Blythe Street veteran nicknamed Smoky, became his right-hand man. “U need feet out here,” Molina wrote to Romo on WhatsApp. “Can’t bee in two places at once if not u probably would.”

Hundreds of messages exchanged between the two men illustrate their relationship: Romo the demanding boss, Molina the fawning middle manager.

On Christmas Eve 2017, Molina typed out a long message: “Don’t let nothing change u Bee. Ure one of the few that I consider a good homie a good camarada so with that said just know ure boy will always Bee loyal & will always have ure back as long as I am around.”

“Gracias for ur words,” Romo wrote back. “They r a gift I accept more than money or shiny objects.”

The crimes that Romo and Molina discussed span the state’s penal code: Collecting money from gambling parlors. Extorting dispensaries. Buying weapons at gun shows with fake IDs. Obtaining drugs in Mexico and trafficking them out of state. Killing an informant within Blythe Street.

The messages reveal Romo’s view of his gang (“an empire”), himself (“a general”) and his management style (“some say I’m too hands on”).

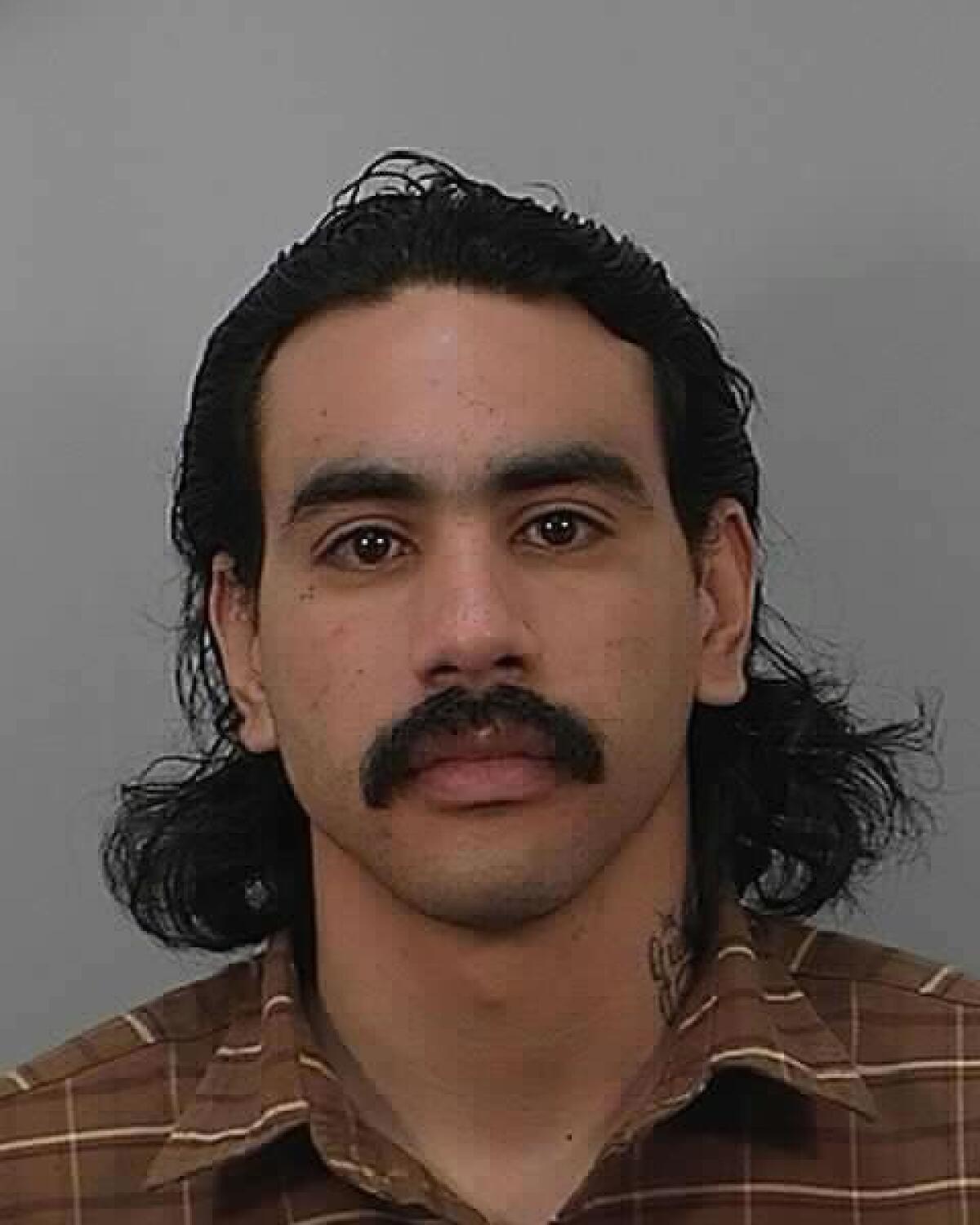

Among the witnesses at Romo’s trial was a man who considered Molina an uncle, even if they weren’t related by blood. Identified in the court record as Witness 2, he was the beneficiary of a remarkably lenient deal — six years in custody for two murders, four years of which he will be allowed to serve under house arrest.

Witness 2 testified he and Molina spoke with Romo over FaceTime almost every day, huddling in the bathroom of Molina’s apartment. During one meeting, Molina told Romo that Carlos Rios, a Blythe Street hanger-on, had gotten a gang tattoo without being jumped in — inducted through a beating.

“Nobody can have a ‘B’ on his face without earning it,” Romo said, according to Witness 2. “This is not a game.” He told Molina to “take care of” Rios, Witness 2 testified, although he acknowledged Romo did not explicitly say to kill him.

Rios had grown up in the gang’s territory and attended Panorama High School until the 11th grade, when he was caught stealing a skateboard and sent to a youth camp, said his sister, who declined to be named. She described Rios as a quiet kid, “very private,” who kept his family and friends separate.

She recalled the day her brother came home after doing a 10-month stretch in county jail with a “B” tattooed on his left cheek. “I was very upset,” she said. Even before he went to jail he’d been claiming to be part of the gang. She doubted it.

That was a Wednesday. By Sunday morning he was dead.

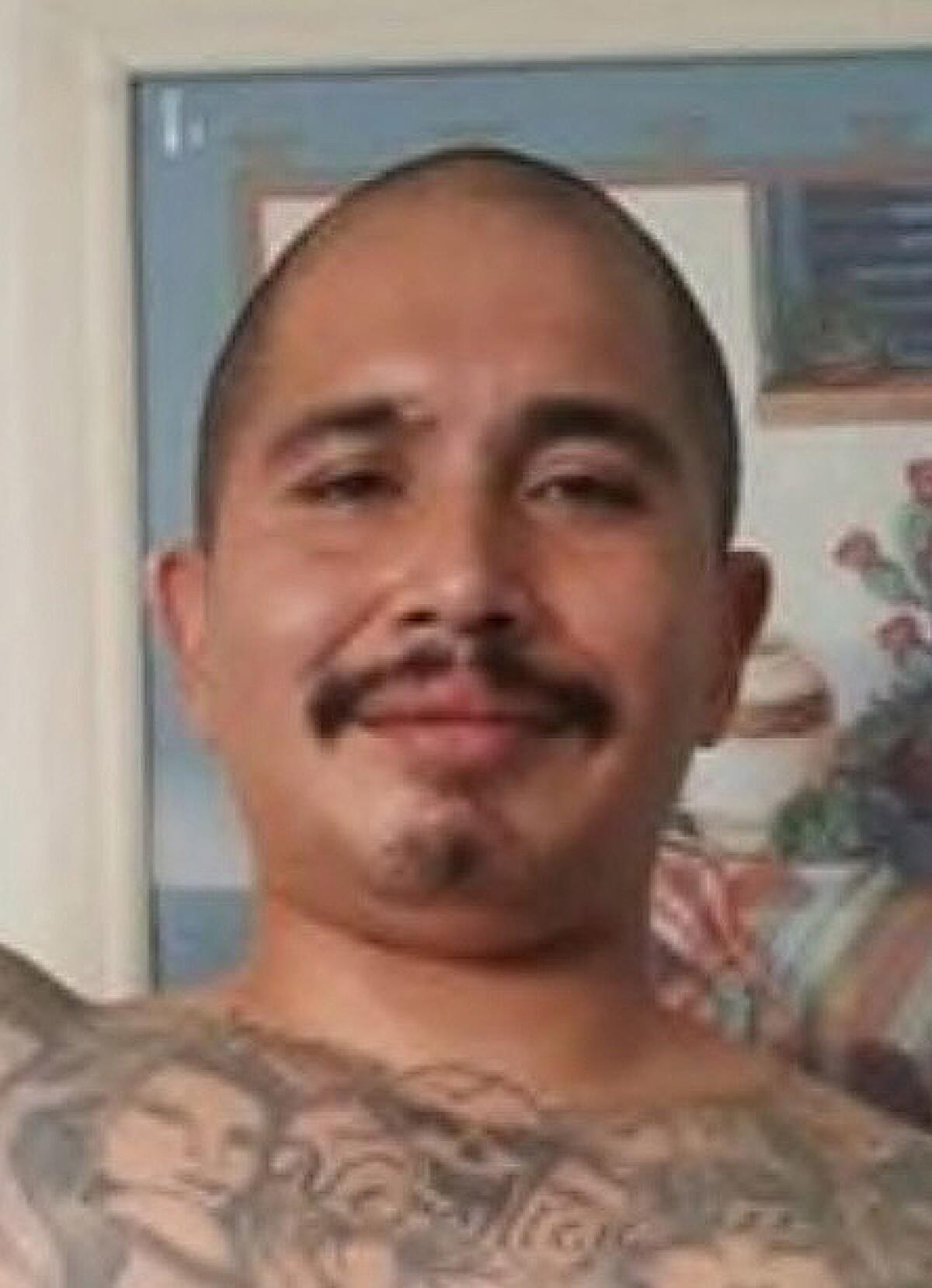

The jury heard the following account of his death from Witness 2 and one of the shooters, Santos “Raider” Martinez, then 18, who bragged to his cellmate in a recorded sting:

Romo was mad that Panorama City was “hot” — had drawn the attention of the police — so Molina, Martinez and his brother, Neftaly Martinez, drove Rios to Van Nuys, telling him they were going to graffiti a rival neighborhood.

Rios started spray-painting “BST, Panorama City, Blythe Street,” Santos Martinez told his cellmate. “I tell him keep on tagging. While he’s tagging, I dome the idiot.”

But Rios was alive, even though Santos Martinez had emptied his gun’s magazine into the 21-year-old. So Neftaly Martinez got out of the car, Witness 2 testified, and finished him off.

Prosecutors also charged Romo in the murders of three people killed in the long-running feud between the Blythe Street and Columbus Street gangs, arguing their deaths ensured he retained control of Panorama City’s drug trade.

The night of Nov. 17, 2017, Alexis Saldana, 18, pulled onto Blythe Street with three other members of Columbus Street in his car, yelling “F— burros,” Santos Martinez told his cellmate. Burro, Spanish for donkey, is a derogatory term for Blythe Street.

Santos Martinez said he chased them to a Wendy’s, where he “took this fool out.” Shot in the back of the head, Saldana stepped on the gas and crashed into the restaurant.

A month later, James “Smiley” Rodriguez, a Columbus Street member whom Molina had warned to stay out of Panorama City, was shot to death outside a Denny’s where Witness 2’s wife waited tables. She testified that after the shooting, Santos Martinez told her a “pobre pendejo” had been killed too. A poor bastard.

Elvis Sanchez had been sitting next to Rodriguez on a bus bench when the shooting started. The 31-year-old deliveryman, who had nothing to do with gangs, died on the sidewalk.

“2 more calabazas down,” Molina wrote to Romo the next day, using an insulting term for Columbus Street. “Everything worked out perfecto once again. And smiley was one of them.”

“Good to know...” Romo wrote. “Gracias b safe!!!”

‘Hood, God, then family’

According to Witness 2, Molina had taken part in five murders. He’d collected Romo’s money and carried out his orders, putting the gang above all else. “For him, it was his hood, God, then family,” Witness 2 said.

His reward was four bullets in the back.

Romo would berate Molina for not returning his calls. “Don’t worry about me u stopped answering me I’m cool won’t bother u no more!!!” he once told Molina, who responded with a long apology. He was tired of them arguing over “simple stuff,” Molina wrote. “It seems like u find the reason to go off on me and I know u do it for my good but u know sometimes I’m not having a good day.”

Molina was addicted to heroin and methamphetamine, Witness 2 said. Sometimes he’d shoot up while he was on FaceTime with Romo.

As South Korea confronts a dark chapter of its history, a former soldier’s quest for repentance becomes a lesson in the fragility of memory.

“There is only 24 hours in a day. Money never sleeps,” an irritated Romo told Molina after several missed calls. He said he assumed Molina had “too much Halloween candy” — drugs.

Around 4 a.m. on Feb. 10, 2018, Molina told a woman in his apartment he would be right back, a coroner’s report says. He tucked a revolver in his waistband, stepped out and was shot in the doorway by his longtime friend, Eder Mendoza, prosecutors charge. Another Blythe Street member, Lorenzo Gonzalez, allegedly acted as the lookout.

Witness 2 testified that Romo told him Molina was killed because he’d owed people money, he’d been caught lying and he “was getting way, way too high.”

Twelve days later, Mendoza and Gonzalez picked up Karen Tobar, 23, in an unlicensed taxi called a “bandit cab,” prosecutors say. Tobar had been in Molina’s apartment the night he was killed. Her body was found in a Sylmar park the next morning, stabbed 60 times.

Mendoza and Gonzalez believed she’d talked to the police about Molina’s death, prosecutors allege. Both men have pleaded not guilty to charges of murdering Molina and Tobar.

‘A real mans worth’

In his closing argument in a ninth-floor courtroom of the downtown Criminal Courts Building, Romo’s attorney, Jerome Haig, said the prosecution’s witnesses were lying when they cast him as “the big leader of this gang, who micromanages everyone.”

From the start of their investigation, he argued, the police wanted to tie every gang killing in Panorama City to Romo, no matter how thin the evidence.

Jurors did not buy it. After deliberating for nine days, they not only convicted Romo of the murders he was alleged to have ordered, but also found him liable for the killings of Columbus Street members. He faces life in prison without parole.

After the verdict, Haig took the view that Romo “was trying to make the gang more powerful as an enterprise, not as far as killing people.” He noted that Romo’s messages with Molina discuss selling drugs, acquiring guns and making money — but none of the murders he was said to have ordered. Making that argument to the jury, though, was “a difficult needle to thread.”

“I tried to make the jury think, and think hard, about their obligations,” Haig said. “And I think they did, even if they didn’t come back our way.”

Santos Martinez, who fell asleep as his attorney pleaded with the jury to acquit him, was convicted of four murders. The panel found his brother guilty of murdering Rios; while Neftaly Martinez was acquitted of Saldana’s murder, he was found guilty of conspiring to commit the crime.

Palm Springs faces a $2-billion reparations claim from Black and Latino families who were burned out of their homes 50 years ago during “slum clearance.”

William “Smokes” Benitez, who “looked like” the third participant in Alba’s shooting, according to Alba’s girlfriend, was acquitted of that murder. The jury hung — 9 to 3 in favor of acquittal — on the charge that Benitez, along with Santos Martinez, murdered Rodriguez and Sanchez outside the Denny’s, said his lawyer, Joel Koury.

Benitez was nonetheless convicted of conspiring to commit those murders, meaning he faces 50 years to life in prison, Koury said. “The way the law is written,” Koury said, “there’s no limit to liability. Because he’s a gang member, he’s responsible for everything the gang does.”

Koury said, in casting so broad a net, the state’s gang conspiracy law fails to consider that people join gangs for different reasons and get involved to varying degrees.

“Since the jury rejected that he was a shooter, what was William Benitez’s role in the conspiracy? He got high with the gang,” Koury said.

It was never made clear during the trial whether Romo got what he wanted. While Haig said he has “no status” in the Mexican Mafia, the word on the street is Romo is now a “señor,” a term of respect for a Mexican Mafia member.

On a recent evening, Blythe Street was quiet. So many of its members are in jail or dead.

Perhaps Romo said it best when he texted Molina, six weeks before he was murdered: “U can judge a real mans worth by the success of those around him.”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.