Newsletter: Essential Arts: Indigenous views of the border in exhibitions in Arizona and New Mexico

- Share via

I’ve spent two weeks tooling around the country in an old Honda while surviving on truck stop coffee and blasting Mexican Institute of Sound’s “Disco Popular.” I saw art. I saw architecture. And I ate a ginormous sopaipilla.

I’m Carolina A. Miranda, arts and urban design columnist at the Los Angeles Times and I’m baaaaaack with your weekly dose of culture news — as well as your essential guide to all things cacio e pepe.

Reckoning with the modern border

Exhibitions about the U.S.-Mexico border can often take on the feel of bilateral dispute. There is the United States and there is Mexico. There are the abstractions of policy and the realities that spur immigration. There is us and there is them. And there is the ever-hardening line in between. But a couple of shows I saw during my recent jaunt through the Southwest upend the idea of border as binary.

“Passage,” which is entering its final week at the Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum at the Mesa Arts Center in Arizona and “Indigenous Women: Border Matters,” on view at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe through early October, expand the frame to center the Indigenous view of the border.

The U.S.-Mexico border as we know it, after all, is a relatively recent invention. Established after the conclusion of the Mexican-American War in 1848, the first formal barriers didn’t begin to materialize until the early 20th century in locations such as California and Arizona — to regulate the movement of people and cattle and to assuage concerns that Mexican revolutionaries wouldn’t appear in the U.S. unannounced.

In fact, it wasn’t until the Clinton administration in the 1990s that the border began to assume its modern look, when steel helicopter landing mats left over from the Vietnam War were used to mark the divides between territories. The architecture of the border has grown increasingly defensive, aided and abetted by the xenophobic rhetoric of politicians like former President Donald Trump, who operated by the mantra, “Build the wall.”

In the meantime, Indigenous groups such as the Tohono O’odham of Arizona, who have inhabited the Sonoran Desert for centuries, have seen their historic homelands quite literally torn apart by the border — sacred sites and environmentally fragile zones blasted away to make way for ever more wall.

Make the most of L.A.

Get our guide to events and happenings in the SoCal arts scene. In your inbox once a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.

“Passage,” which was organized by curator Tiffany Fairall at the Mesa Contemporary Arts Museum examines the toll the border has taken on human life in an installation that also nods to O’odham tradition. The exhibition features the work of artist Cannupa Hanska Luger (an enrolled member of the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation) in collaboration with Indigenous and Mexican artists from around the Southwest and beyond.

The exhibition’s principal and most moving work consists of thousands of unfired clay beads that have been strung in a labyrinthine pattern from the ceiling. “Something to Hold Onto,” 2019-21, as the installation is titled, was conceived by Luger but is an eminently collaborative work.

Thousands of contributors submitted handmade clay beads from locations around Arizona and the country, with each bead intended to symbolize a life lost along the U.S.-Mexico border over the last 30 years. Luger also teamed up with two local Indigenous artists — Thomas “Breeze” Marcus (Tohono O’odham) and Dwayne Manuel (Onk Akimel O’odham) — who contributed a floor mural inspired by O’odham creation myths.

Viewers are invited to navigate this labyrinth, coming into intimate view with the beads, which bear the distinct imprint of thousands of human hands. The effect is bone-like and funereal, a veil of manufactured death hovering over the O’Odham imagination.

The taut and tiny “Indigenous Women: Border Matters” at Santa Fe’s Wheelwright, organized by curator Andrea Hanley, also looks at the ways in which modern notions of the border have disrupted Indigenous life.

Installations and paintings by M. Jenea Sanchez and Gabriela Muñoz (both of whom identify as Latinx) pay tribute to Indigenous women living in the border town of Agua Prieta who work collectively to share knowledge on a range of cultural and economic issues. And a series of wry linocut prints by Makaye Lewis (Tohono O’odham) capture the vagaries of life along the border — in which to be Indigenous is to be suspect and to be subjected to the continuous surveillance of border authorities. Strangers on their own land.

Particularly visceral is an installation by Daisy Quezada Ureña (Mexican American), whose featured works depict articles of women’s clothing — principally undergarments — hung on plastic spikes that emerge from the wall. In some cases, she renders the clothing in porcelain, which gives these personal items an unsettling, ghostly sheen. Another sculpture by the artist features a woman’s shirt supported against the wall by a metal fence post.

Redolent of sexual violence, the sculptures are a gripping memento mori to the steep bodily price often paid by female immigrants to the United States.

These are difficult subjects. But even as these exhibitions offer an unblinkered view of the ways in which policy can play out in real and violent ways, they also reflect the ways in which artists and communities can come together — to work, to tell a story and to show resilience in the face of political forces that don’t see people, only the imaginary geopolitical line.

Cannupa Hanska Luger, “Passage,” is on view at the Mesa Arts Center in Mesa, Az., through Aug. 8; mesaartscenter.com. “Indigenous Women: Border Matters” is on view at the Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian in Santa Fe through Oct. 3; wheelwright.org.

Art report

The Times’ Christopher Knight checked out both parts of L.A. artist Alison Saar‘s two-part survey “Alison Saar: Of Aether and Earthe,” on view at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena and the Benton Museum of Art at Pomona College, and reports that the shows are “enthralling.” “The artist has been an eloquent, poetic chronicler of Black womanhood for more than 30 years,” he writes. “Together, the exhibitions confirm Saar’s stature as among the finest American sculptors working today.”

There’s a silk sunflower shortage — and that’s because they’ve been vacuumed up by the “Immersive Van Gogh” exhibition that’s about to land in Los Angeles. Deborah Vankin put on her hard hat and headed to the former Amoeba Music building in Hollywood to get a gander at the $39 experience (36% more than regular admission to LACMA), where a friend mournfully notes that the actual Van Gogh likely wouldn’t have been able to afford the sugar cookies now being sold in his name. Don’t get too excited going to see Gogh, though. As of Friday, the opening date had been delayed by at least a day since “Immersive Van Gogh” had yet to receive its certificate of occupancy from the fire department.

Ace Gallery founder Douglas J. Chrismas was arrested on Tuesday on federal charges that he embezzled more than $260,000 from his gallery’s bankruptcy estate. The Times’ Jessica Gelt has the deets on the case — as well as a rundown on Chrismas’ long string of legal troubles.

Enjoying this newsletter? Consider subscribing to the Los Angeles Times

Your support helps us deliver the news that matters most. Become a subscriber.

Plus, the New York Times has an extensive report on the Artist Pension Trust, which was intended as a way to help establish financial security for artists by pooling the sales of their work. Artists — many of them from Los Angeles — are now alleging that the company has made few payouts, moved their work without notification and has generally been unresponsive to their concerns.

Performing arts

Times theater critic Charles McNulty recently received a note from the father of a playwright who was not pleased to see his son’s work panned in the Los Angeles Times. In a meditation on the nature of criticism, McNulty responds to the man: “Criticism is part of the field. He will get negative reviews in the future along with high praise. He should take only what he finds useful and reject the rest. Playwrights and critics work on parallel tracks. We are both trying to enrich the art form, even though at times it can seem as if we’re on opposing sides.”

“Edges” is the early song cycle written by Benj Pasek and Justin Paul, who would later become famous for their hit Broadway show “Dear Evan Hansen.” Now the show is being revived by the Chance Theater in Anaheim and its premise is a simple but enjoyable one, writes The Times’ Daryl H. Miller: “No phalanxes of strutting, spinning circus performers here. Just four performers, singing their hearts out.”

Broadway’s theater owners and operators announced Friday that they will require masks and a COVID-19 vaccine of audiences attending performances.

L.A. theaters are doing much the same. If you want to see “Hamilton” when it opens at the Hollywood Pantages Theatre next month, reports Jessica Gelt, you will be required to show proof of vaccination. In addition, children under 12 must show proof of a negative COVID test and children under 5 will not be admitted. The Pantages joins a growing number of L.A. performance spaces that will require audience members be vaccinated.

Classical Notes

The L.A. Phil is back in the Bowl with a summer program that features plenty of concerts conducted by Gustavo Dudamel, along with shows led by six former Dudamel Fellows, a program in which young conductors are chosen to work as assistants. A Bowl debut is always “a nail-biter,” writes Times classical music critic Mark Swed and this week provided debuts that were both exhilarating and bumpy, with first turns at the podium by Tianyi Lu and Enluis Montes Olivar.

William Robin at the New York Times has an interesting piece about Nadia Boulanger, a 20th century composer-turned-teacher who became known as “a one-woman graduate school so powerful and so permeating that legend credits every U.S. town with two things: a five-and-dime and a Boulanger pupil.” An upcoming festival at Bard College will bring greater attention to her music.

Design time

The structures that William Pereira designed for LACMA are demolished and gone, right? Wrong. Last year, artist Cayetano Ferrer extracted numerous pieces from the museum’s Modernist facade and will employ them in a new park design for West Hollywood. The design toys with ideas of the folly ruin, but also adds a palpable layer of history (albeit ersatz) to the L.A. landscape. “That’s really the most important part of this,” he tells me. “This is a very privatized city and there aren’t a lot of spaces like public plazas where that might occur, where the past might be layered upon.”

The fragments go on view in Pasadena for a one-day show on Saturday afternoon.

Times home design writer Lisa Boone has a great bit on a beautiful backyard writing studio in Elysian Heights that blends Spanish Revival and storybook architecture to create a singular space. Am I jealous? Yes, I am.

Plus, Nate Berg has an interesting story in Fast Company about how the Tokyo Olympics’ design goes beyond aesthetics: in these games, it’s all about accessibility. (Too bad no one can attend.)

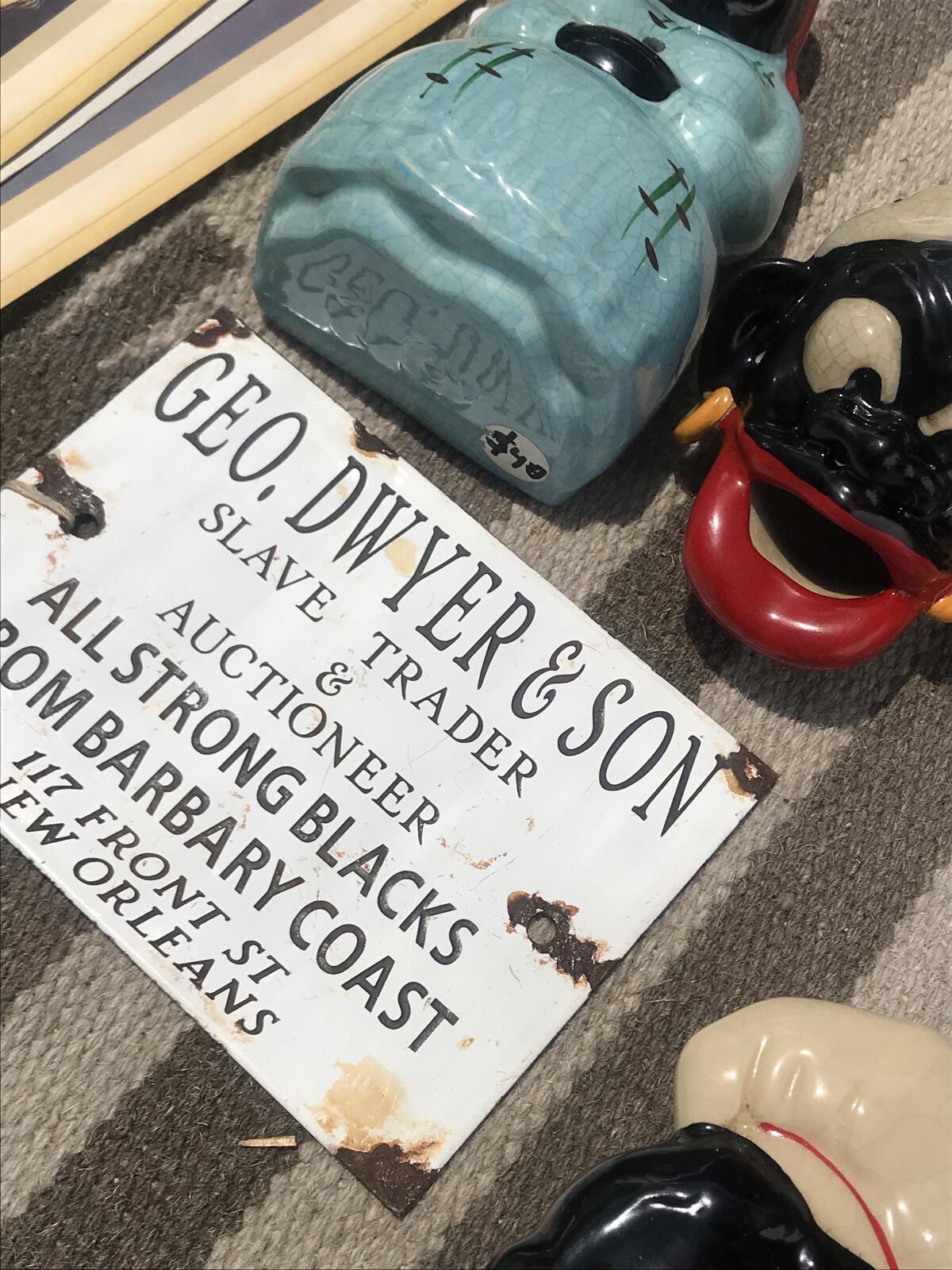

Trafficking in racism

The Times’ Makeda Easter paid a visit to the Rose Bowl Flea Market recently only to be confronted with racist, anti-Black memorabilia, including minstrel dolls and a sign advertising a slave trading business. She speaks to David Pilgrim, founder and director of the Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia at Ferris State University about the phenomenon. “My work,” he tells her, “is about making it so there would be no demand, so that folks would recognize the harm that are done by these objects.”

Essential happenings

The weekend is here, which is a good thing because so is Matt Cooper‘s list of 13 best bets for the weekend, including a series of livestreamed performances by the Actors’ Gang and a screening of “The Princess Bride” set to live music courtesy of the L.A. Phil. Always a hard yes to Mandy Pantikin as Inigo Montoya.

Ex post facto

Because I am the queen of hitting shows on the last day, I didn’t see “Not I: Throwing Voices (1500 BCE — 2020 CE),” the permanent collection show organized by curator José Luis Blondet at LACMA until last Sunday. I just wanted to note what a wild and enjoyable show it was — a riff on ventriloquism and the ways in which one voice may speak for others.

Drawing from across regions and time periods, it contained juxtapositions that were hilarious (say, an 18th century bust of a crying child from the Netherlands next to a 1930s baby monitor designed by Isamu Noguchi), as well as poignant (composer Raven Chacon’s sound piece, drawn from whistles in LACMA’s collection).

Also intriguing were the Goya prints contained in wooden frames carved by contemporary L.A.-based artist Patricia Fernandez, who was born in Spain. Her hand-tooled frames, boxes and structures are inspired by her grandfather’s carving style. (She was recently the subject of a solo show at Commonwealth and Council.) The installations felt like an easy conversation between artists that just so happens to be taking place across centuries.

Also, what a relief it is to see artists of color showcased in an exhibition that isn’t about some sort of social turmoil.

Sadly, the show is closed, but LACMA’s blog, Unframed, has a good interview with Blondet about how the show came together. “Ventriloquism seems to be akin to the logic of the encyclopedic museum, in which objects are speaking on behalf of an entire culture, age, or region,” he says. “Issues of identity, embodiment, performance and objecthood are at the core of even the most conventional ventriloquist sketch: Where is the voice coming from? How is that voice split into many bodies? Whose voice is this? Who is speaking on behalf of whom?”

In other news

— A fourth suicide at Thomas Heatherwick’s “Vessel” sculpture in New York City is raising questions about why better barriers have yet to be installed.

— In May, Ela Bittencourt published a report in Frieze that noted that Brazil has lost various cultural institutions over the years to fires and flooding because of willful government neglect and that its priceless Cinemateca Brasileira was at risk. Sadly, that reality has now come to pass.

— Arts funding gets a boost in the latest budget for the state of California.

— LAXART is seeking Charlottesville’s removed Jim Crow-era statues for an exhibition that would include responses by contemporary artists. (While I was in Charlottesville, Va., I saw the site where the statue of Robert E. Lee once stood.)

— Travis Diehl reports on the hard-won rise of Latinx artists in Los Angeles.

— And, L.A. artist Cassils is selling cans of poop based on the diet of top-grossing white male artists as an NFT.

— There are turf squabbles afoot over the Smithsonian’s National Museum of the American Latino.

— Mark Lamster comes through with a great review of a very unusual building.

— Infrastructure week: How old Inca roadways still deliver benefits to the inhabitants that surround them.

— Museums are jumping on TikTok; but Hyperallergic’s Stephanie Stacey writes that it’s the small ones who are doing it best.

And last but not least ...

Since we’re on the subject of social media: my aim in life is to channel this cat’s vibe.

———————————————

Aug. 1, 2021 3:05 a.m. For the record: An earlier version of this newsletter said Ace Gallery founder Douglas J. Chrismas was arrestedy on charges that he embezzled more than $260 million from his gallery’s bankruptcy estate. The alleged amount of money in the case is more than $260,000.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.