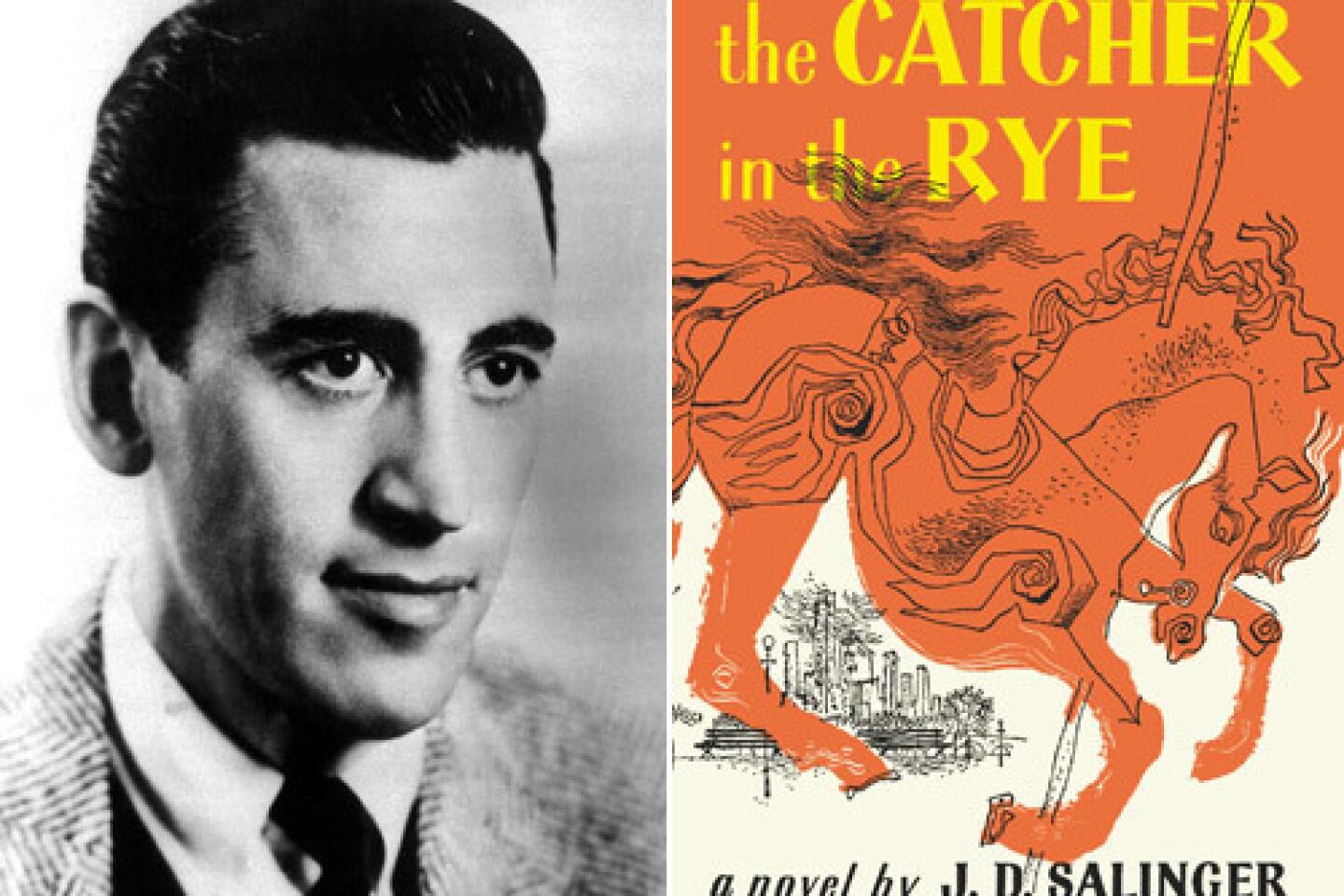

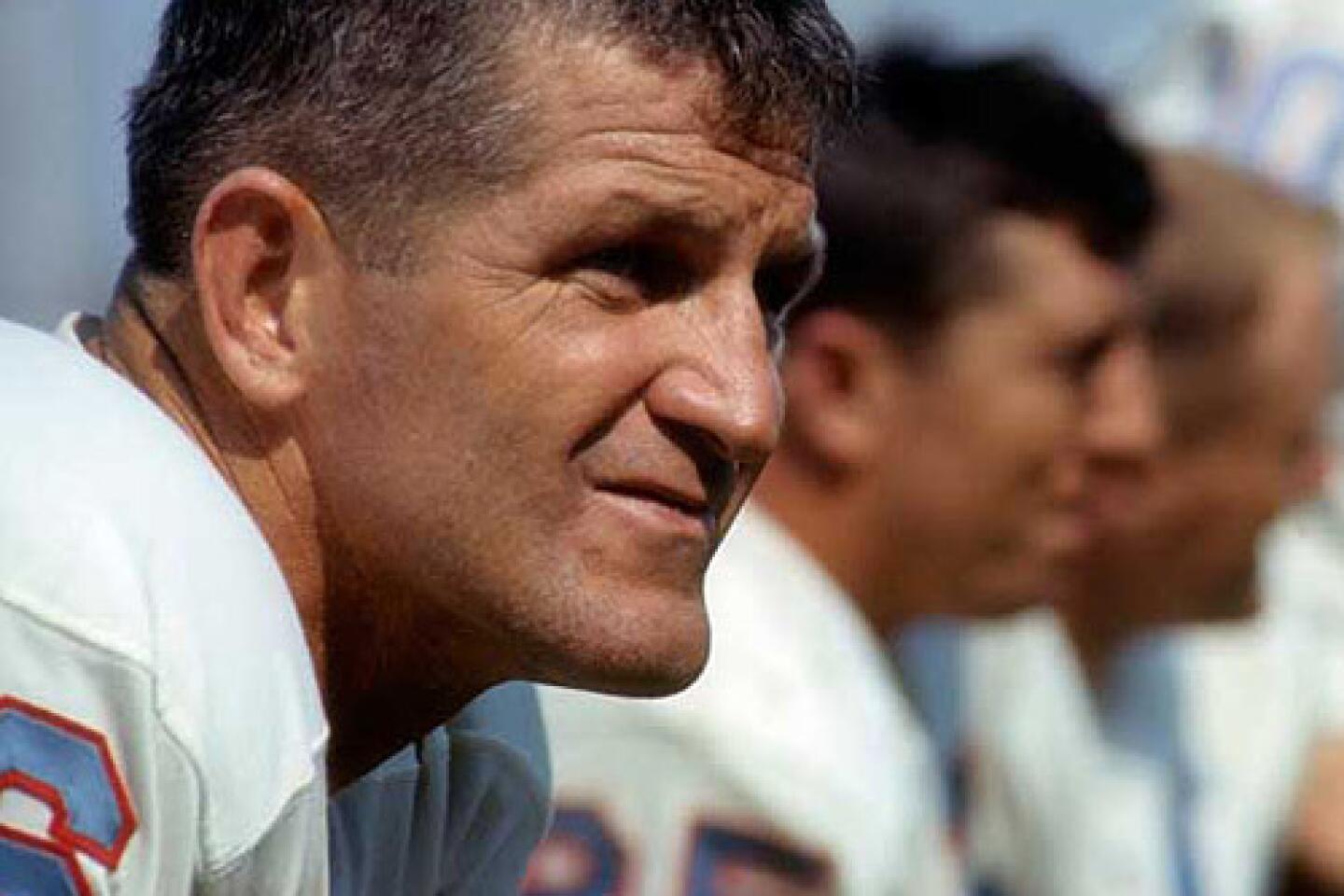

Bob Feller dies at 92; Cleveland Indians pitcher was one of baseball’s greats

- Share via

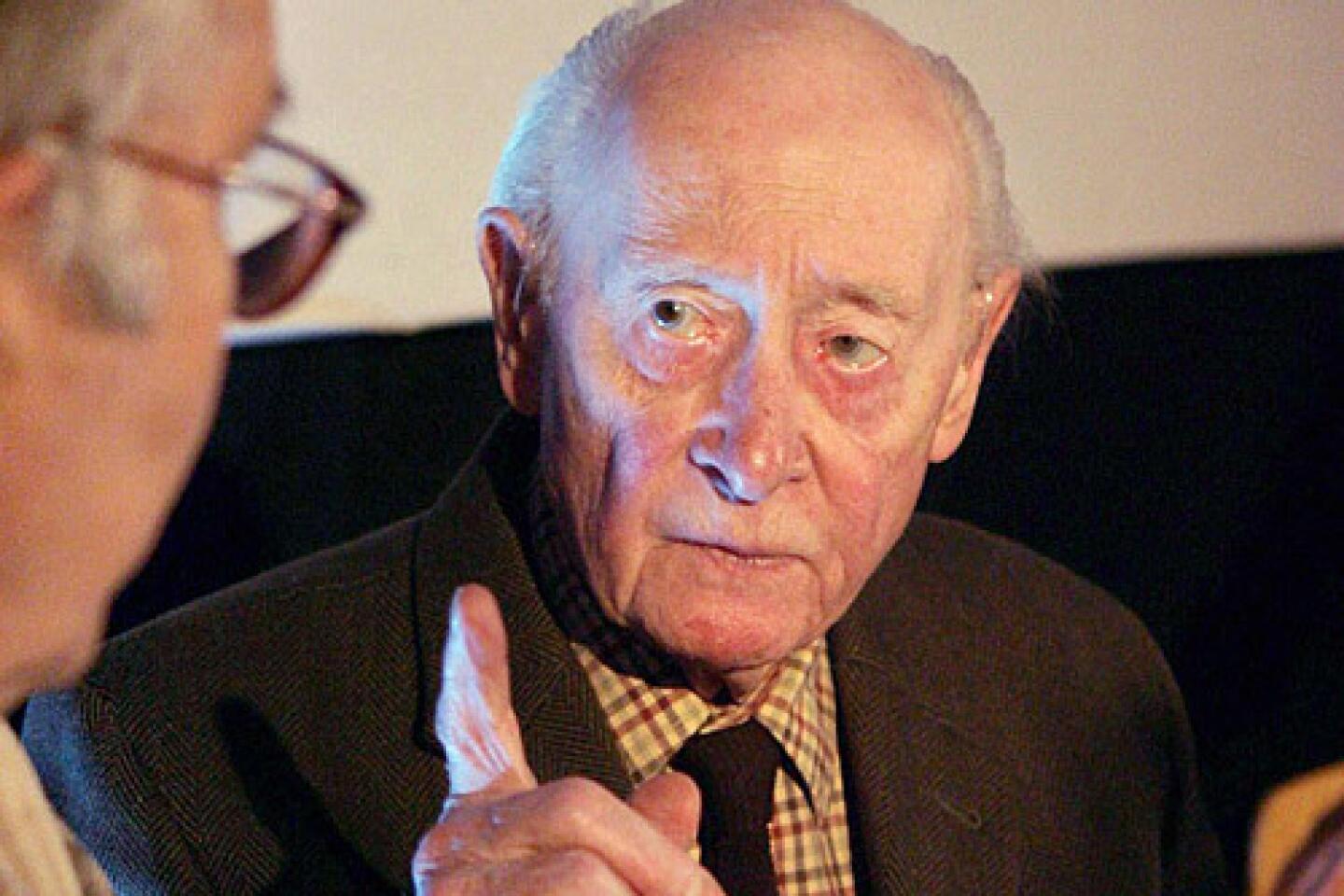

Bob Feller, an Iowa farm boy who became one of baseball’s most enduring stars as an overpowering pitcher for the Cleveland Indians, died Wednesday. He was 92.

Feller, who was elected to the baseball Hall of Fame in 1962, died at a Cleveland-area hospice, the Indians said. He was diagnosed with leukemia in August and more recently was hospitalized with pneumonia.

FOR THE RECORD:

Bob Feller: The obituary of baseball Hall of Famer Bob Feller in the Dec. 16 LATExtra section said he was the first pitcher to throw three no-hitters. Feller was the third major leaguer to pitch three no-hitters in his career. Larry Corcoran was the first and Cy Young was the second. —

Feller won 266 games from 1936 to 1956 for the Indians, a remarkable achievement given that he spent more than three full seasons serving in the Navy during World War II. He was the first pitcher to toss three no-hitters, including one on opening day. Feller led the American League in strikeouts seven times and won 20 or more games in six seasons.

Not only did Feller have a better fastball than anyone else during his era, but he kept hitters off-balance with a variety of pitches. And his motion featured a high leg kick that further distracted the opposition.

“Feller was the best pitcher I ever saw,” Hall of Fame slugger Ralph Kiner told New York Newsday in 1989. “He threw as hard as [ Nolan] Ryan and had a better curve.”

His significance went beyond the pitcher’s mound. He was an early labor leader as the first president of Major League Baseball’s Players Assn. He organized lucrative barnstorming games between major league players and stars of the Negro Leagues. And he understood his power as a star.

When Clark Griffith, the owner of the lowly Washington Senators, wanted to time Feller’s fastball before a game in 1946, the right-hander refused to take part in the publicity stunt until he negotiated a fee for his services. Feller was paid $700 and his fastball was clocked at 98.6 mph.

Robert William Andrew Feller was born Nov. 3, 1918, to Bill and Lena Feller at the family’s farmhouse in Van Meter, Iowa.

By the time he was 8, Feller could throw a curveball and by 9 could throw a ball more than 270 feet, according to John Sickels, who wrote “Bob Feller, Ace of the Greatest Generation” (2004).

Feller’s father went to considerable lengths to develop his son as a baseball player.

“Few fathers rigged the second floor of their barn up as a makeshift baseball throwing range for use during the winter and few fathers altered their business practices to leave more time for baseball,” Sickels wrote. Bill Feller switched his crop to wheat instead of corn because wheat didn’t take as much time to farm.

By 1931, father and son were building their own baseball field on the family property.

“We cut down 20 trees, put the posts in the ground, put up the chicken wire and built the ballpark,” Feller told the Cleveland Plain-Dealer in a 2010 interview. “We peeled the infield and fenced off the outfield to keep the livestock off.” His father organized teams for Feller to play with and against.

There was no doubt how important baseball was to the Fellers.

“We started out as Catholic but the priest told my father not to play baseball with me on Sundays,” Feller told the Akron (Ohio) Beacon Journal in 2007. “We became Methodists.”

Feller was 16 when he signed with Cleveland in July 1935. He was supposed to start the 1936 season in Fargo, N.D., once his junior year of high school was finished. But he struck out eight of nine St. Louis Cardinals he faced in an exhibition, and a phenom was born.

He struck out 15 St. Louis Browns in his first start that summer and in a September game tied the major league record with 17 strikeouts against the Philadelphia Athletics.

By 1938, he was an All-Star and won 17 games for the Indians. He won 24 games in 1939, then went 27-11 in 1940, pitching a no-hitter on opening day against the Chicago White Sox at Comiskey Park.

Ted Williams, the Boston Red Sox left fielder considered one of baseball’s greatest hitters, once said: “Three days before he pitched, I’d start to think about Robert Feller.... I’d sit in my room thinking about him all the time.”

Feller won 25 games for the Indians in 1941, then enlisted in the Navy two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor. Licensed to fly, he wanted to be a fighter pilot but couldn’t pass high-frequency hearing tests. He volunteered for combat duty and was assigned to the warship Alabama as a gunboat captain in the Pacific.

“For all he accomplished in baseball, and all baseball means to him, I still think Bob’s more proud about his service in the Navy,” Feller’s wife, Anne, told Sports Illustrated in 2007.

Just don’t call him a war hero.

“Heroes don’t return from war,” Feller told USA Today in 2007. “It’s a roll of the dice. If a bullet has your name on it, you’re a hero. If you hear a bullet go by, you’re a survivor. There are millions of survivors.”

His military service clearly cut into Feller’s career statistics, but years later he said he was “proud to be part of a much bigger victory.”

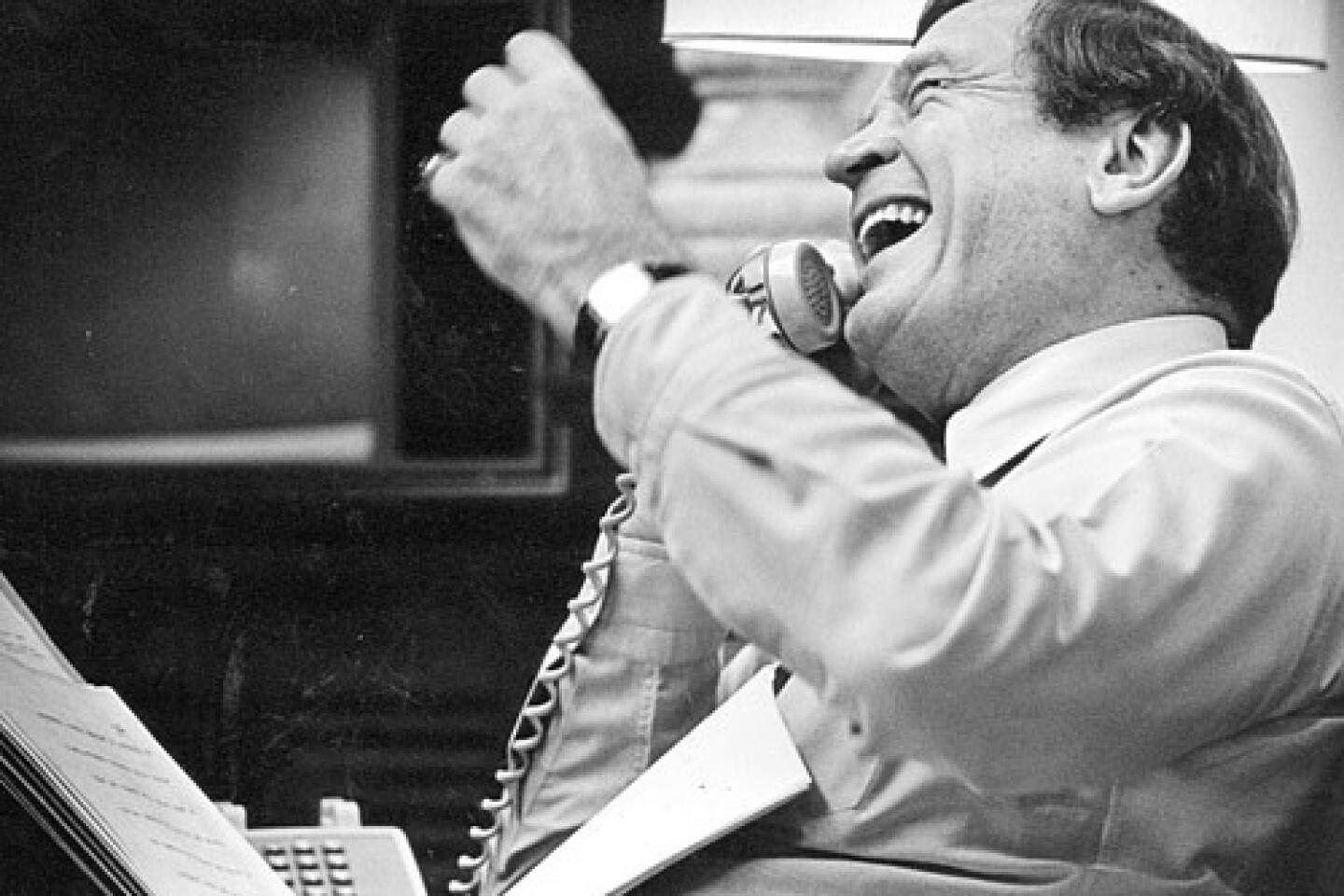

The pitcher dubbed “Rapid Robert” and “Bullet Bob” returned to the Indians in time for nine starts in 1945, then had a memorable season even by his standards in 1946.

Feller went 26-15 for a team that won only 65 games. He pitched 36 complete games, including his second no-hitter, and pitched in relief six times, a test of durability that would not be asked of a pitcher today. Feller said he came into the season in great shape after an extended cross-country barnstorming tour that he organized with major league players facing Negro League stars.

The 1946 tour included such big leaguers as Stan Musial of the St. Louis Cardinals and Phil Rizzuto of the New York Yankees. The Negro League stars included pitcher Satchel Paige and first baseman Buck O’Neil.

Feller convinced A.B. “Happy” Chandler, then baseball’s commissioner, to increase barnstorming days after the World Series from 10 to 30 “so guys could make some money they lost in World War II,” he told the Cleveland Plain-Dealer this year.

“Feller was a meticulous man and personally saw to everything that mattered, including transforming himself into a corporation — Ro-Fel — and checking receipts at each stop,” wrote Larry Tye in his 2009 book “Satchel: The Life and Times of An American Legend.” According to Tye, Feller earned $80,000 from the 1946 tour.

There were differences over money. Paige and later Jackie Robinson said they weren’t paid what they were owed. It didn’t help that Feller was quoted in the Sporting News disparaging the abilities of the Negro League players. Some of Feller’s views evolved over time and by the 1960s he publicly pressed for Paige’s inclusion in baseball’s Hall of Fame. Years later he was still feuding with Robinson, however.

In 1947, Feller won 20 games for the fifth time, then reached the World Series for his only appearance in 1948. Feller had a 19-15 record for the Indians, but two other pitchers — Bob Lemon and Gene Bearden — each won 20 games. Cleveland beat the Boston Red Sox in a one-game playoff to reach the World Series, then defeated the Boston Braves in six games. Feller lost both his World Series starts.

He won 22 games and pitched his third no-hitter in 1951, then had his last high-quality season in 1954 with 13 victories. He retired in 1956.

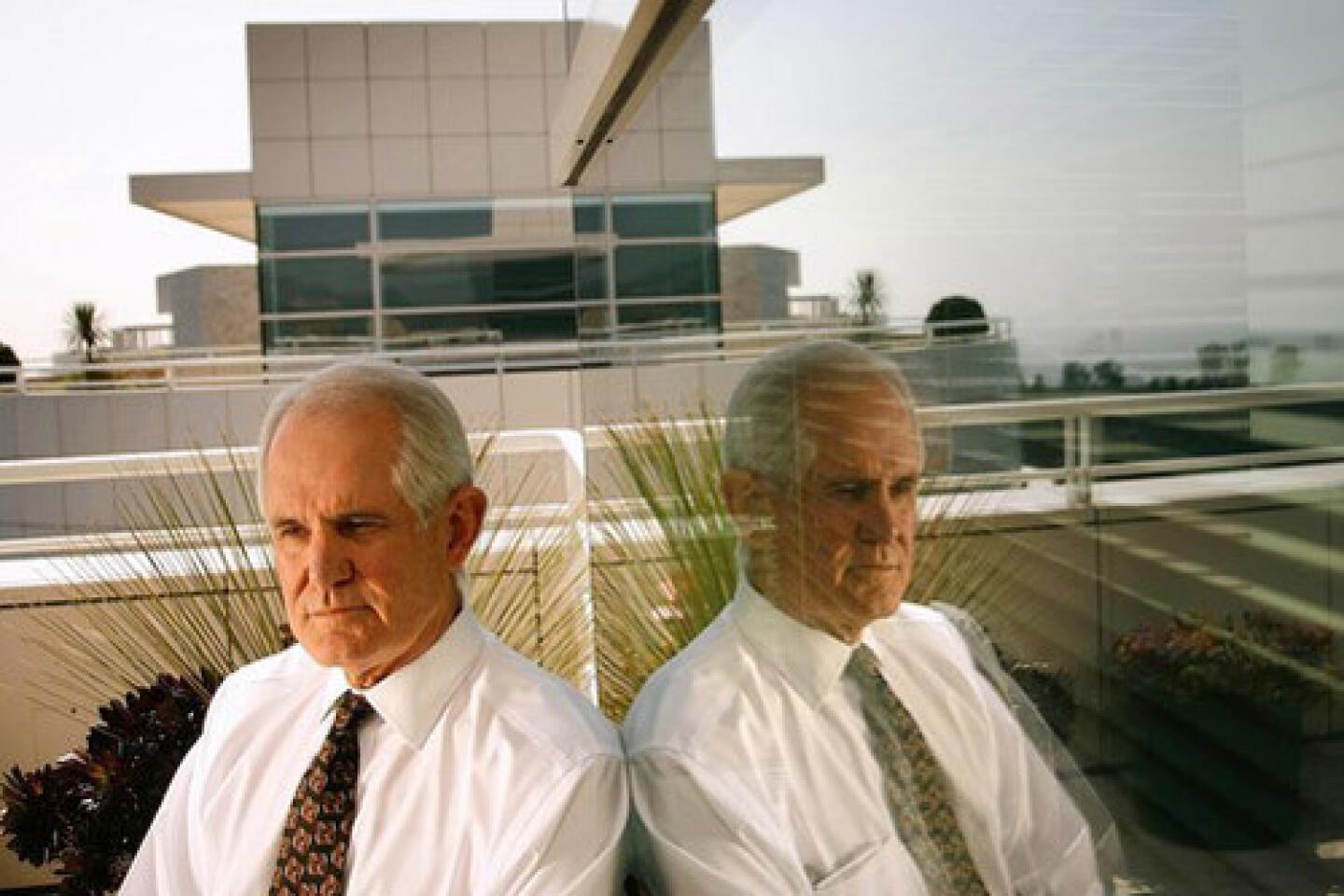

Feller rarely hesitated to speak his mind. As early as the 1950s he advocated changes in baseball’s reserve clause, a system that gave owners complete control over signing and releasing players. “They call baseball the great American pastime, but what is more un-American than tying a player to a club against his will?” he said in 1957. He said owners trying to move franchises were “loud-mouthed magnates.”

He remained active into his 90s, signing autographs, making speeches and talking about baseball, often critical of today’s players and what the game had become. He worked as an ambassador for the Indians and in 2009 pitched in the first Hall of Fame Classic in Cooperstown, N.Y.

“I’m a promoter,” he told the New York Times in 1986. “People say, ‘Well you’re out promoting Bob Feller.’ Well, who else would I be promoting?”

In addition to his second wife, Anne, Feller’s survivors include sons Stephen, Martin and Bruce from his first marriage to Virginia Winther, which ended in divorce.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for the L.A. Times biggest news, features and recommendations in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.