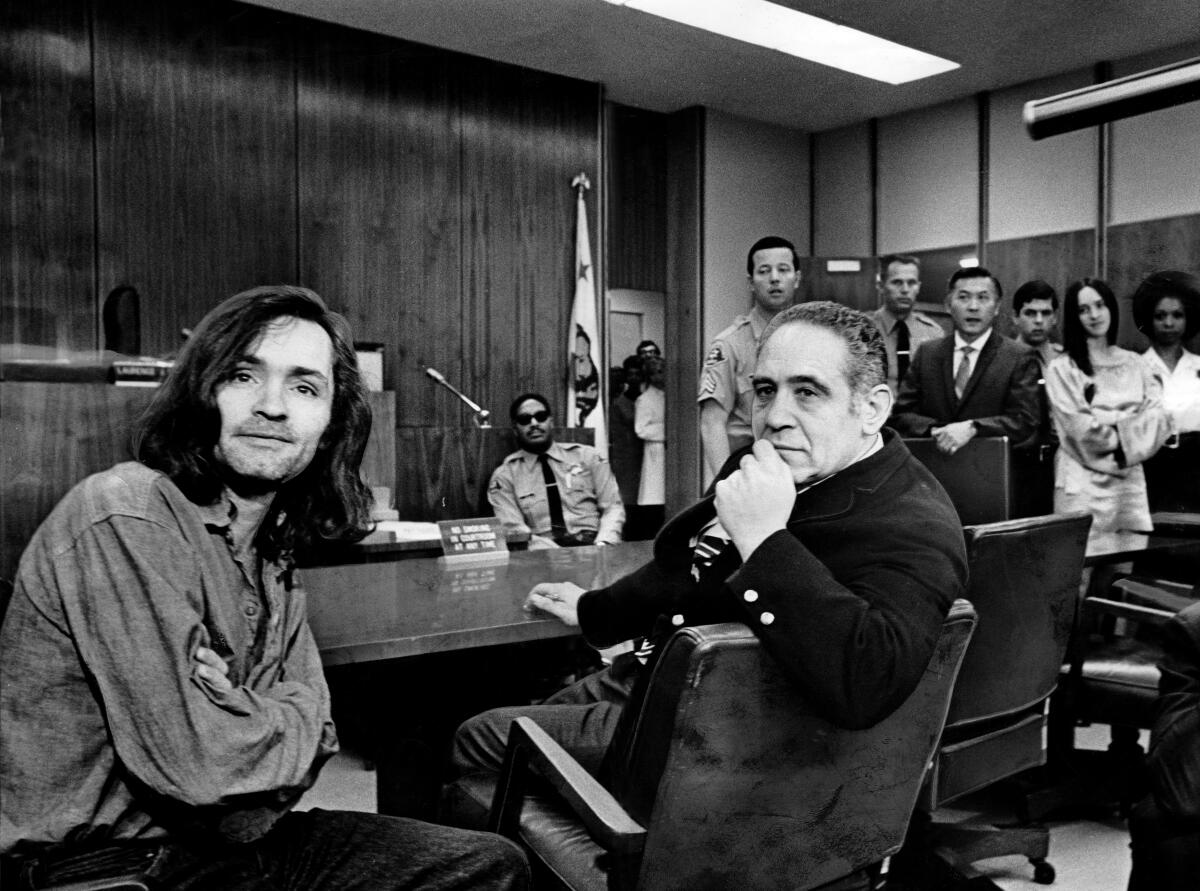

Irving Kanarek, hard-charging attorney who defended Charles Manson, dies at 100

- Share via

Irving Kanarek, the hard-charging and bombastic criminal defense attorney who represented Charles Manson and argued through the decades that his notorious client had nothing to do with the gruesome Tate-LaBianca murders, has died at age 100.

Kanarek, who had battled colon cancer, died Sept. 2 in Garden Grove, his daughter Irvina Kanarek said. The cause was old age, she said.

In the courtroom, Kanarek was a force of nature, sometimes to the extreme. During the Manson trial, he was loud, argumentative and objected repeatedly to questions, answers and even the prosecution’s opening statement. When he took the case, the Los Angeles County district attorney’s office worried the trial would be reduced to “a circus.”

They weren’t far off. The trial lasted nearly a year and was a spectacle from start to finish. Manson lunged at a bailiff and taunted the judge. Defendants Susan Atkins, Leslie Van Houten and Patricia Krenwinkel laughed, doodled on legal pads and arrived in court with Xs carved into their foreheads. And by the third day of testimony, Kanarek had already objected nearly 300 times to questions, often bellowing at the court.

When the state’s star witness, Linda Kasabian, was called to the stand, Kanarek snapped: “I object, your honor, on grounds this witness is not competent and she is insane.”

Though largely dismissive of Kanarek, prosecutor Vincent Bugliosi admitted in his book “Helter Skelter: The True Story of the Manson Murders” that he regarded the attorney as a worthy foe. “The press focused on his bombast and missed his effectiveness.”

Manson and his followers were convicted in 1971 and sentenced to death, the 19-year-old Van Houten becoming the youngest woman at the time to be sent to death row. The following year, their death sentences — along with the sentences of every other California inmate on death row — were commuted to life in prison when the state Supreme Court briefly ruled capital punishment illegal. Atkins died in prison in 2013; Manson died in 2017, also while still behind bars.

Near the close of the 1960s, everyone who kept up with the news knew who Charles Manson was, but hardly anyone had heard of Vincent Bugliosi.

The years after the Manson case were at times turbulent ones for Kanarek. He admitted he “flipped out” after barging into the district attorney’s office in Torrance and was eventually handcuffed by police and admitted to Harbor-UCLA Medical Center for psychiatric evaluation.

Kanarek told former L.A. Times columnist Dana Parsons in 1998 that he also spent several years in a “rest home” dealing with personal problems. By the time he returned to his law practice, he said, it was in ruins. During his absence, the State Bar had paid out claims filed by three former clients, leaving him more than $40,000 in debt. Not long after, he gave up his license.

“They’ve done a Salman Rushdie on me,” he said, referring to the author who was handed a death sentence from Iran’s spiritual leader for writing the book “The Satanic Verses.”

At the time, Kanarek said he was living in a Garden Grove motel, had no car and was getting by on Social Security checks. Unlike Bugliosi and others, Kanarek refused to capitalize on his famous client, whom he defended again and again.

“He was a personable guy,” he said of Manson. “He had nothing to do with those murders.”

Kanarek stayed in touch with Manson over the years, his daughters said, and was emphatic that writing a book or profiting off the case would compromise his attorney-client obligations and put him in a no-win position of revealing information he regarded as confidential.

Kanarek was born May 12, 1920, in Seattle, one of two children. He earned a degree in chemistry from the University of Washington and worked in the aerospace industry until he lost his security clearance after he was accused — falsely — of being a communist. He sued and his security clearance was restored, along with his back pay.

Intrigued by the law, he attended Loyola University and was admitted to the California Bar in 1957. One of his early clients was Jimmy Lee Smith, who, with Gregory Powell, kidnapped a pair of police officers and killed one of them in an onion field near Bakersfield. The case was depicted in Joseph Wambaugh’s 1973 book “The Onion Field.” Smith died in jail in 2007 while serving time for a parole violation.

The Manson case was an extraordinary opportunity and challenge for Kanarek, offering the veteran of civil and criminal law both national exposure and a difficult uphill legal battle. Kanarek insisted that the media, the prosecution and ultimately the jury had prejudged his client as a hippie with a deep fondness for drugs and sex, lifestyle choices he said had nothing to do with the case.

The back-to-back nights of murder occurred in August 1969, when Manson ordered his followers to go to a house in Benedict Canyon and kill “everyone inside.” The carnage was staggering. Actress Sharon Tate, eight months pregnant, was stabbed to death and hung from a rafter. Hair stylist Jay Sebring, aspiring filmmaker Wojciech Frykowski and coffee heiress Abigail Folger were also stabbed to death, as was a young man who was visiting the estate’s caretaker.

The following night, Manson asked his followers to do it again, and this time rode along with them as they drove through the city, finally picking a house in Los Feliz at random. Inside, Leno and Rosemary LaBianca were dozing on the couch when Charles “Tex” Watson and Manson forced their way in. They tied up the couple and assured them it was just a robbery and neither would be hurt. Then Manson stepped outside and the killing begin.

The girls of the Manson ‘family’ drove a chill deep into the nation’s psyche that has yet to lift.

During the long trial, Kanarek attacked the state’s case with vigor and took calculated risks, even showing jurors photographs of the barbaric murder scenes, reasoning they’d see the images soon enough during deliberations. “Let’s face the facts here,” he told the court.

After Manson and his followers were dispatched to death row, Kanarek filed an $11-million libel suit against Bugliosi, alleging the prosecutor’s book inaccurately portrayed him as “a bumbling, stumbling, foolish, ridiculous attorney.” The case was ultimately dismissed.

Irvina Kanarek said her father was often unfairly portrayed because of fleeting moments in a long career — a mental breakdown and financial distress, among them. “These are private moments that are a part of many Americans’ lives,” she said.

The daughters said they recalled their father as a warm and funny person, someone who always had “a one-liner in his back pocket.” He had a fondness for museums, especially the Getty and Huntington, and had an encyclopedic knowledge of the streets of L.A.

Later in life, Kanarek told the Guardian that he continued to reflect on the Manson case. Asked why an attorney would represent someone accused of such loathsome crimes, Kanarek said he’d do it again if given the chance.

“I would defend a client who I knew was guilty of horrific crimes,” he said. “They have to be proved guilty. I’ve had cases where people were guilty as hell but they couldn’t prove it. And if they can’t prove it, he’s not guilty. That’s American justice.”

Kanarek is survived by two daughters, Irvina and Walesa.

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.