Column: Great news for victims of L.A.’s drug war: Your cannabis convictions will soon vanish

- Share via

In 2016, California voters resoundingly said they wanted adults to be able to grow, sell, process, transport and use cannabis recreationally without fear of prosecution. The passage of Proposition 64, the Adult Use of Marijuana Act, was a watershed moment in this country’s long, tortured history of waging a failed war on drugs.

For the activists who worked so hard to get the proposition on the ballot, there was another equally important aspect of the law: Anyone who had been convicted of a crime tied to cannabis would be released from jail or prison, and anyone with a conviction on their record — whether it was recent or happened decades ago — would be eligible to have it expunged.

In 2018, California enacted a law requiring prosecutors in every county to review state Department of Justice data on convictions and to take steps to dismiss them. The law gave prosecutors a July 1, 2020, deadline.

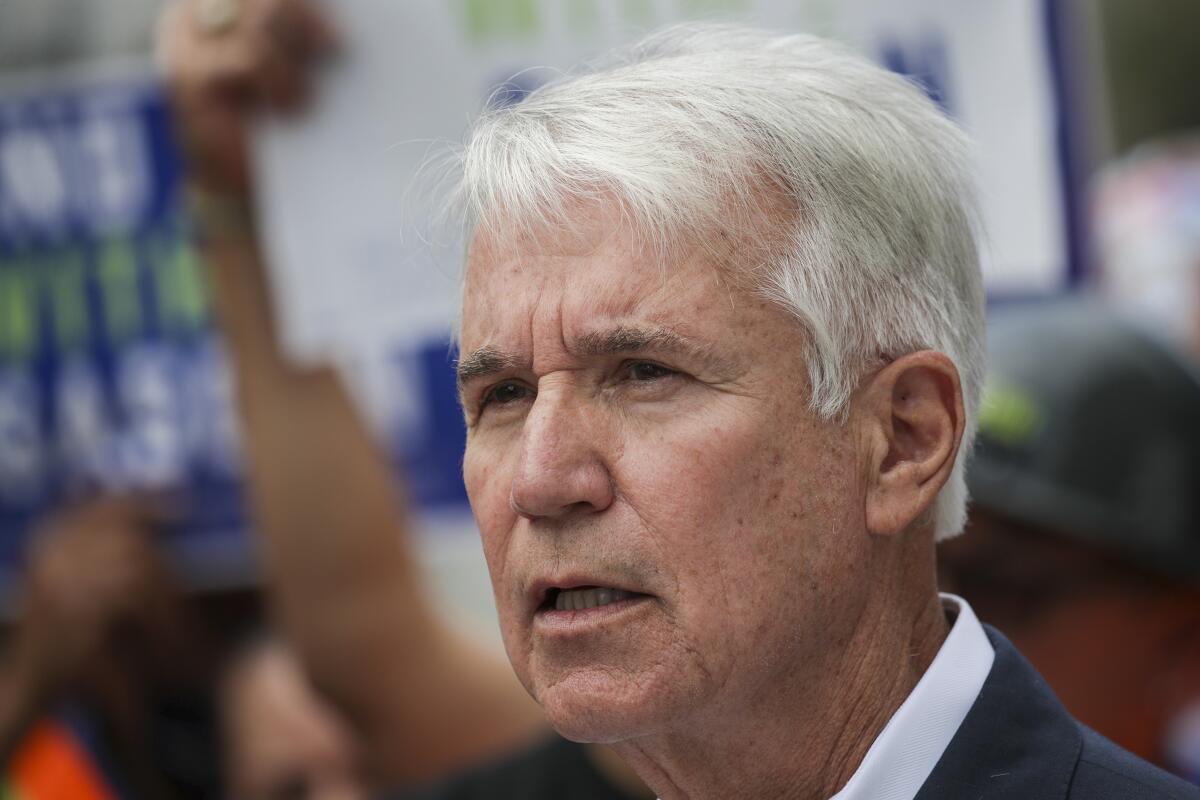

Los Angeles County Dist. Atty. George Gascón, a co-author of Proposition 64, has been at the head of the pack. On Monday, he made a stunning and welcome announcement: In addition to the approximately 66,000 Los Angeles County residents whose convictions were dismissed last year, another 58,000 who had been identified through an examination of county court records, would be forgiven.

Not only will convictions be expunged, Gascón said Monday, but records in all the cases will be sealed.

No longer will someone convicted of a cannabis crime in L.A. County have to “check the box” on an application or admit to a potential employer or landlord that they have ever been convicted of a cannabis-related crime.

L.A. County Dist. Atty. George Gascón will dismiss the marijuana-related convictions of nearly 60,000 people and seek to have their criminal records sealed.

“This is a new day,” said Lynne Lyman, a criminal justice reform activist who is also a co-author of Proposition 64. “People take it for granted that L.A. is a liberal place, but that hasn’t always been so.”

::

I think it’s fair to say that the rollout of adult recreational use of cannabis in California has been plagued by problems.

The obstacles include absurdly high state and local taxes and the chaos caused by giving local jurisdictions complete control over whether to issue licenses for any type of cannabis business within their boundaries.

Not incidentally, the illegal cannabis market continues to flourish as officials have stumbled around trying to create a legal and logistical framework these last few years.

The law is supposed to make it possible for people penalized by the drug war, such as those who have now been forgiven, to get priority when they apply for local cannabis licenses. In addition, applicants who live in communities hard hit by the drug war are also supposed to be able to receive priority for licenses under the city’s “social equity program.”

In Los Angeles, it hasn’t worked out that way.

“The biggest issues are capitalism and greed,” said Lyman. “You are working against a market force that is tremendous.” In places such as South L.A., she said, predatory investors put out flyers offering $5,000 to partner with someone who could qualify for a social equity license. And then, she said, “in three years, under the right of first refusal, the ‘investors’ get to buy the company,” forcing out the original applicant.

“This has happened to tons of people,” Lyman said. “There are so many people being taken advantage of.”

Unscrupulous investors were able to step into the breach, she said, because the city focused first on giving out licenses, rather than providing technical and legal assistance or financing opportunities, for folks ill-equipped to review contracts or raise money on their own. (I’ll address this issue in a future column.)

Still, we cannot overlook some of legalization’s greatest successes.

Besides wiping the slate clean for those convicted of pot crimes, Lyman said, no one is in jail or prison in California on pot charges alone. Since Proposition 64 took effect, she told me, nearly 12,000 people have been released.

And there is also the important issue of what is called “community repair.”

Proposition 64 created the California Community Reinvestment Grants Program, which is funded with $50 million a year in state cannabis tax revenue. (State officials said last month that the state collected $817 million in cannabis taxes in the 2020-2021 fiscal year; that amount does not include the revenue collected by cities and counties.)

The state money goes to groups serving populations that have been disproportionately affected by cannabis laws. It will come as no surprise that many of these people are in low-income areas with large Black and Latino populations.

Last year, in L.A. County alone, 23 organizations were awarded about $12 million in state money, in amounts between $240,000 and $900,000.

The money went to groups such as ReIgnite Hope, which trains students for careers in welding; the Watts Labor Community Action Committee, which created MudTown Farms, a community center that feeds people and teaches them how to grow their own food; and Starfish Stories, which offers housing and support services to dozens of formerly incarcerated men.

“This is one of the beautiful, untold positive stories of Prop. 64,” Lyman said.

Cities and counties were supposed to create similar funds, she said, but most have instead funneled cannabis revenue into their general funds, which, ironically, means a windfall for police departments.

“They are setting crazy high taxes at the local level, and state taxes are already too high,” Lyman said. “The city of Los Angeles is the worst offender.” The city is bringing in $158 million this year in cannabis revenue, and all the money is going to the general fund.

Lyman and others involved in creating Proposition 64 are working on a new proposition for voters. This one is aimed at getting cities and counties to pony up their fair share of cannabis tax revenue to the folks who need it most. That list may be long, but it most definitely does not include the police department.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.