A doctor was arrested for warning China about the coronavirus. Then he died of it

- Share via

BEIJING — He sent warnings of a deadly virus on social media. The Chinese government moved to downplay the emergency, but Dr. Li Wenliang’s insistence on telling the truth turned him into a folk hero in a country that prizes secrecy and crushes dissent.

Li and seven other whistleblowers were arrested for spreading rumors. Only last week, as the coronavirus outbreak kept 50 million Chinese people on lockdown and accelerated around the world, did authorities concede that Li and the others should not have been censured.

“It’s not so important to me if I’m vindicated or not,” Li, 34, said in an interview from a quarantine room with Chinese publication Caixin. “What’s more important is that everyone knows the truth.”

Li’s vindication seemed even more meaningless after news that he died early Friday in a hospital in Wuhan, the center of an epidemic he warned about in December. Conflicting accounts about his condition echoed through official channels and across social media, adding another layer of confusion in a government that appears increasingly overwhelmed. Early reports of Li’s death were retracted when the hospital said it was working to save his life.

Hours later, he was officially reported dead.

Li left behind his wife and one child. Chinese internet users flooded social media with an outpouring of grief, calling Li a hero, a victim and a martyr. They demanded apologies from those who had arrested him and asked that the national flag be flown at half-staff.

His death was the latest tremor in an unprecedented crisis that has spread beyond public health to public trust in China. The virus is exposing cracks in the political system with near-daily revelations of corruption, ineptitude, inefficiency and lack of transparency and accountability at the cost of people’s lives.

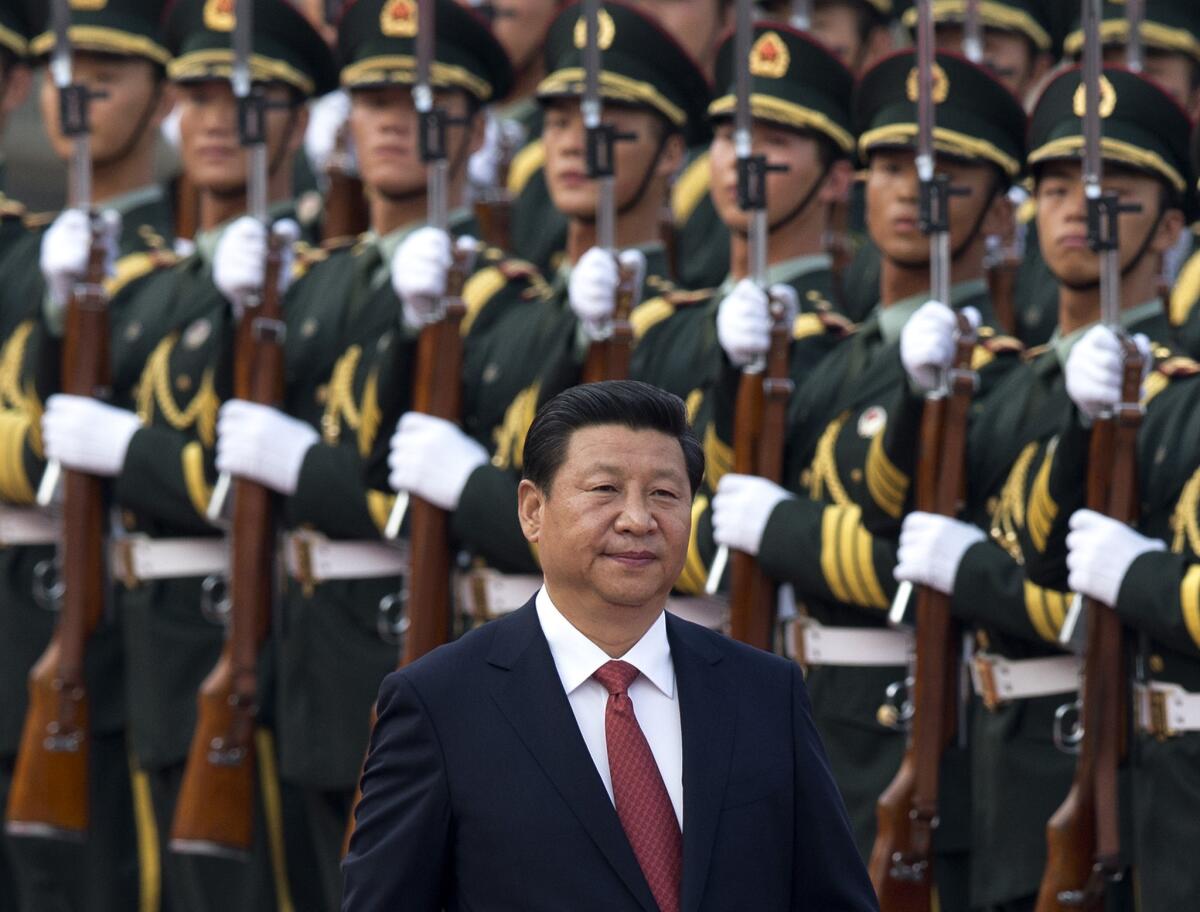

It has also damaged President and Communist Party Chairman Xi Jinping’s self-portrayal as a loving father figure bringing wealth, power and rejuvenation of the great Chinese nation under his leadership. His favorite tools of governance — control, propaganda, nationalism, and force — are failing to provide what Chinese people need most now, and what Dr. Li symbolized: reassurance that their lives are valued and that they will be given the truth.

Weeks into China’s coronavirus outbreak, there are no signs the crisis is under control. The confirmed infections in China have surpassed 30,000 and continue to jump by the thousands, turning each day into an eerie tick-tock of who might be next. More than 630 people have died, and reports abound of sick Hubei residents who died “outside the numbers,” untested and thus uncounted within official coronavirus records.

China is now a nation under self-imposed house arrest, its cities frozen, streets emptied, roads blocked and villages locked down. Authorities have ordered Wuhan to set up mass quarantine centers for those infected. Guards check temperatures at the entrances to residential compounds that feel hollow without the usual sounds of children playing and neighbors taking walks.

But inside, online and especially within the epidemic’s epicenter in Wuhan, anguish and fury are growing, inflamed by an ugly reality: that authorities prioritized saving face and appearing in control over the health and safety of their people — and that they continue to do so now.

Within an hour of Li’s death, the trending topic “Wuhan government owes Dr. Li Wenliang an apology” on the social platform Weibo was censored.

The gap between propaganda and reality — and government and people — has become more apparent in the last two weeks. State TV broadcasts have been a steady stream of praise for the party’s leadership. Chinese journalists and online activists, meanwhile, have exposed government-backed charities in Hubei for mishandling donations of medical equipment, diverting protective masks to private organizations and for officials’ use rather than sending them to frontline hospitals in dire need.

On Thursday, reports of local officials trying to steal one another’s masks went viral: Officials in Dali, a southwestern city, tried to intercept a shipment meant for Chongqing. And in Qingdao, officials ordered customs to seize masks meant for Shenyang.

The most efficient organizations at coordinating donations have ironically been celebrities’ fan clubs, the only sort of grass-roots organization still allowed under Xi’s crackdown on civil society as he moves to consolidate his power.

Their outperformance of the government and official organizations has played out live on the internet. Critical posts are moving faster than censors while hundreds of millions of Chinese people are stuck at home doing nothing except reading, swiping and growing angry.

Xi has ruled with an unrelenting grip since his political ascent in 2013, silencing lawyers, activists, journalists and liberal intellectuals, wiping out civil society, centralizing power under the party, erasing his own term limits and enshrining his “Xi Jinping Thought” into the constitution.

That has raised concerns from dissidents and grass-roots groups on the margins of Chinese society, but not shaken his power in the mainstream, in part because Xi has so adroitly mobilized Chinese propaganda and education to stoke nationalism.

Those who criticize the government or seek “Western” values such as human rights and freedom of the press are often sidelined as foreign-funded, self-hating Chinese impeding the motherland’s rise.

Even with other recent challenges — a U.S.-China trade war, unrest in Hong Kong, Taiwan’s assertion of sovereignty, and global criticism over Xi’s detention of Uighur Muslims in concentration camps in Xinjiang — Xi has managed to hover above public criticism, often by blaming “foreign intervention.”

But now Xi faces the biggest challenge yet to his rule and the party’s legitimacy: a preventable crisis that is striking Chinese families dead, shows no sign of stopping and cannot be blamed away.

Worse, the virus is a natural disaster, something that could have come straight out of imperial history books, where the Chinese people recognized earthquakes, floods, plagues and other heaven-sent crises as a sign that their emperor was ruling unjustly and had lost his legitimacy. When disaster struck, it signaled that a dynasty was about to end — and when the masses lost faith in the emperor, uprisings soon followed.

This might be the moment Xi loses that “mandate of heaven,” said Orville Schell, historian and director of the Asia Society’s Center on U.S.-China Relations. It’s not something quantifiable, he added, like a percentage change in GDP growth or specific number of infected cases or deaths. It’s a psychological shift, a loss of trust in the rulers’ ability to protect the people.

“Xi Jinping is a leader who has led — and not unsuccessfully, I can say — by control. And now he’s confronting something he cannot control,” Schell said.

China is ramping up censorship after the coronavirus outbreak. Police dressed in hazmat suits to ‘quarantine’ a man, then took him to a police station.

“If you’re looking at the equation of what makes a leadership have legitimacy, and be functional and effective, a lot of it depends on whether people believe in it and have faith in it. If they believe in some way that it’s running out of gas, or reaching the end of some cosmically ordained cycle, that’s pretty difficult to fix.”

That loss of faith resounds most for those trapped in Wuhan, a city many see as being sacrificed against its will, without any apology or responsibility taken by the authorities. It is a sequestered place of rising deaths caught in the gaze of an anxious nation.

“We won’t talk politics, but you must let me speak of my suffering,” said Lu, 57, a woman in Wuhan whose father died of the coronavirus on Monday, and whose mother and sister are sick with lung infections and fevers as well.

Lu said in a phone interview that she’d spent three days calling emergency hotlines, the city government, hospitals, neighborhood committees, pulling every connection she could find to get her 83-year-old father a hospital bed.

He’d fallen sick in early January, when officials were still saying the virus was not contagious between humans. By last week, he was struggling to breathe and bleeding in his digestive system, but still unable to check into a hospital.

“There are 10,000 people trying to get 1,000 beds. How can you get one?” she said. “I’ve never felt so hopeless, seeing my mom and dad with no way to be treated. Seeing all those people in the hospital ... why didn’t they control it? How could you, the government, just lightly say it wasn’t contagious? Why not be more serious, and put people’s lives first? Now you can’t clean it up. How big is the loss to the country, to the people?”

While her father was dying, Lu kept seeing state media reports about available hospital beds and wards, hotlines for patients and the country’s great mobilized effort to save Wuhan.

“The media are so beautiful, everyone thinks I’m making up rumors online. People outside don’t know,” said Lu, who didn’t give her full name. When friends sent her reports about help for her family, she’d reply: “It doesn’t exist.”

Lu’s mother, 80, is now quarantined alone with a high fever. She calls Lu every day, begging for her daughter to come over, but Lu can’t visit her for more than a few minutes, afraid that she might get infected and then infect her own children. Lu struggles to breathe, her anxiety compounded by the silence and isolation.

“Wuhan is just an empty city now. There are no people outside, and no sounds. It’s never been so quiet,” Lu said. “I don’t care who is leading this country. But as a commoner, I want the right to live, to exist in this world. This is the most basic thing. Why shouldn’t I speak about it? Should I just watch my parents die with my own eyes? Where are we supposed to bring our anger?”

More to Read

Sign up for Essential California

The most important California stories and recommendations in your inbox every morning.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.